Travel reveals the most fascinating places. Surreal. Otherworldly. And more often than not, unexpected. Don’t you agree?

My most recent experience that fell into this category was a candy-coloured, turn-of-the-19th Century, European-styled neighbourhood in the nondescript, dusty town of Sidhpur in Northern Gujarat. It was almost bizarre in its very existence. What added to the drama of this completely out-of-place ensemble was that it was abandoned and padlocked, and has been so for years, save a handful or so of its houses.

Much written about in recent times by various bloggers and writers, with even an entire photo exhibition on it by the celebrated Sebastian Cortés in Mumbai in 2015, the place still took me by surprise. I was like, “Is this real?” Even to the extent of touching a few walls, and checking the efficacy of a few locks. I must confess I could not decide what was more hypnotic. The opulent, antiquated mansions. Or the outback, deserted, dusty mantle.

The neighbourhood belongs to a community called the Dawoodi Bohras, a sect in the Ishmaili branch of Shi’a Islam. For those of you unfamiliar with the intricacies of Islam, Muslims are not one homogenous whole despite the claims. Broadly divided into Sunnis and Shi’as based on who was believed to be Prophet Muhammed’s successor, Shi’as divide themselves further into multiple sub-groups depending on their Imam’s line of succession.

In India, Dawoodi Bohras are predominantly found in Gujarat. With just over one million followers worldwide spread over Pakistan, Yemen and East Africa, the closely-knit, tightly controlled community is led by a Da’i al-Mutlaq who currently operates from Mumbai.

I came across Bohra Muslims for the very first time after moving to Mumbai itself, hit most by their women’s characteristic, colourful garbs called rida. But their distinctiveness spans much more as I learnt soon after.

It straddles their language [Lisan al-Dawat—a mix of Gujarati, Urdu, and Arabic], script [Perso-Arabic], food, prayer [they pray only three times a day], and the one I found most interesting—their acute sense of community wherein each stands up for the other through community kitchens, housing projects, and sharing of debts. The last perk only applies so long as you do not marry outside the community.

The early 1900s saw the Dawoodi Bohras growing exponentially in affluence as they explored new ports for trade. One of the most stunning legacies of this was the homes they built themselves in their hometowns—the European-styled vohrawads.

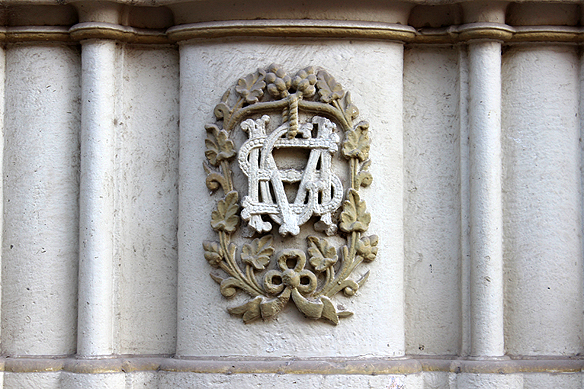

Lofty, narrow, 3-4 storey high row houses lining wide streets in a gated community, their “mahals” [palaces] were painted in vibrant ochres, coral pinks, sage greens, and powder blues. The facades were decorated with elaborate monograms, neo-classical pilasters, pointed gables, panelled wooden shutters, and exquisite iron railings. Forever close to their roots, Indian architectural concepts such as open courtyards and outside window seats were seamlessly stitched into the architecture. Belgian chandeliers, gilded mirrors, and Edwardian furniture completed the interiors.

As oft happens, however, urbanization is rarely reversed, and those who move to greener pastures rarely come back. With each passing generation those who left grew in numbers, and those who stayed back thinned out and the lovely edifices were eventually reduced to “ancestral” homes that were locked away in a forgotten past.

Engrossed in these thoughts, wandering awed and aimless, I saw one door slightly ajar, and hesitantly asked the elderly lady seated by the window, “Must be scary living all alone in this empty lane.” She immediately shook her head. “No. Not at all. There are three houses still occupied in this street. Together we make sure everyone’s home is still safe.” Seeing my confusion, she broke into a huge smile. “This is my home. How can it be scary? I grew up here.” I took her picture though she made me promise I would not use it. I assured her I won’t and it was just for me.

Down the isolated road I bumped into her husband, an elderly, bearded, bent over, bespectacled gentleman in a long kurta and topi. “I saw you took a picture of my wife. Please send it to me. Please.” “Of course, I will. What is your email address?” He scratched his head, and then his beard. “I don’t have one. Just send it, my child. Whichever way you can. Just send it. I very much want to have a picture of her.” I wanted to give him a hug. He reminded me of my dad with his craggy brows and ingenuous grin.

By this time the sun was starting to sink behind the houses and dusk was creeping in. I was three hours away from Ahmedabad. I figured I should leave.

The vohrawads of Sidhpur are not protected by any government agency and are slowly being torn down. Yet many stand, almost defiant, in the wake of time supported by a trickle of determined residents like the couple I met. The question one is forced to ask is for how long would their efforts last before this less-than-ordinary slice of “global” heritage is wiped out in the name of modernisation, only to be unseen by future generations.

Uncomforted by any answers, I took my seat in the car for the long drive ahead of me, looking back at the padlocked houses overwhelmed with nostalgia. Yes, Sidhpur took me by surprise. It was nothing close to what I expected. Either in its edifices or the emotion it evoked in me.

European facades for Indian homes. The vohrawads brought in east-west fusion to the small town of Sidhpur in Northern Gujarat over a hundred years ago.

Though most of the homes are now deserted and locked up, some were open. Less dishevelled and dusty. But no less suspended in the past.

With names like Surat Wala, Husena Manzil, and Zainab Manzil, the edifices are not merely brick and mortar, but are vibrant homes named after real people, and their loves and lives.

Sidhpur past and present. Disparate and disconnected.

Not many young people live anymore in the vohrawads. Most have migrated to bigger cities and greener pastures, leaving their parents behind in their ancestral homes.

1918. A young man must have built this home with much feeling fuelled by much ambition. No differently from his neighbours. Sidhpur gave its Dawoodi Bohras roots as they spread their branches.

The gentleman who wanted me to send him his wife’s picture. 🙂 I promised her I wouldn’t put her photo on the net, so here is his instead.

A handful of residents keep the spirit of Sidhpur alive. Large, grey padlocks lock the rest of the little town’s memories away.

Travel tips:

- Sidhpur is 30 kilometres east of Patan. You can club it together with Modhera and Patan, visiting Sidhpur on the way back.

These houses are incredibly beautiful. Reminds me of locked up mansions of Marwari businessmen in Rajasthan. Similar fate!

LikeLiked by 1 person

They are indeed absolute stunners. Where exactly in Rajasthan are the locked-up mansions you mention? Would love to have a dekko at them some day.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The entire Shekhawati region is famed for these. There are other locations nearby. Let me know when you are headed this side, it is still not yet discovered and written by the blogger fraternity like Shekhawati is.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Now the undiscovered part is what I would love to see! 🙂 Will definitely connect with you when I plan my travels for Jaipur and its immediate surrounds. Thank you for the tip. Appreciated.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Anytime, Rama! 🙂

LikeLike

Just Google on Mandawa, Ramgarh, Nawalgarh. That’s Shekhawati region

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have read lots of posts and articles on the Shekhawati region. Quite a writers’ and photographers’ favourite it is. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

In last 10 years this region has become bloggers and travelers favorite! I don’t find it very exciting because we have similar architecture here but not painted like the ones in Shekhawati.

LikeLike

That’s a good story, sir.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for visiting my blog. 🙂 Happy to know you enjoyed the post.

LikeLike

Nice buildings.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, they are an interesting global fusion. 🙂

LikeLike

Incredibly beautiful heritage, houses and your blog. 💛

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yup to the first two, and a big thank you for the third. Welcome to my blog AmdavadiChidiya. I hope you continue to enjoy reading my posts. I often tell my friends India doesn’t need designated heritage sites. The whole country, in its entirety, needs to be listed as one. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not really a traveller and therefore I didn’t know much about northern Gujarat, but thoroughly enjoyed reading this post (The different side of Gujarat), so well explicated. Loved it. Adding this place to the bucket list! 🙂

LikeLike

Welcome to my blog, Nutty. Thank you for stopping by and your lovely comment. Sidhpur, and in fact all of Gujarat is a traveler’s dream. Am sure you will love it. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Also, Great pictures!!!

LikeLike

Thank you. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

And visiting this place next month 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

You will love it. It is a photographer’s delight! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gone through your Article. And that story of old man 👌. If you haven’t given her wife’s photo, might be I can help. Actually we are working on a local guide from same community who can help us explore these houses. She might be knowing this man as they are of same community. Just incase.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What’s your email ID? Would be great if you could give him a print of the picture. 🙂

LikeLike

hirenkhambhayta@gmail.com

LikeLiked by 1 person

Will try my best

LikeLiked by 1 person

Have mailed them to you. 🙂

LikeLike

Got it, will update more details in mail.

LikeLike