This post is not a political article. It is a travel feature. But to fully understand certain places in our world, it becomes essential to know their political contexts. Why they are the way they are. The answers are invariably in their political history. Such is the case for South Africa, Israel … and Vietnam.

A major event in world history, what the world refers to as the Vietnam War, the Vietnamese call the American War, and history books call the Second Indochina War. But this war actually has four perspectives: That of North Vietnam, South Vietnam, America, and the world at large. Also, this war was not just between Vietnam and America, but between North and South Vietnam as well.

Confusing? Read on.

![The photo that stopped the war: Pulitzer prize-winning photograph 'The Terror of War,' also known as 'Napalm Girl,' Associated Press, 8 June 1972. [War Remnants Museum, Ho Chi Minh City]](https://ramaarya.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/vietnam-war-napalm-girl.jpg)

The photo that stopped the war: Pulitzer prize-winning photograph ‘The Terror of War,’ also known as ‘Napalm Girl,’ Associated Press, 8 June 1972. [War Remnants Museum, Ho Chi Minh City]

To understand the war better, one needs to go back to where it all began. The late-1800s and France’s colonization of southeast Asia which led to the creation of French Indochina comprising Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam.

From 1884 to 1954, all of Vietnam was under the French who were quick to decorate its key cities, Saigon [now Ho Chi Minh City] and Hanoi, to suit their own tastes and needs. Up came grand cathedrals reminiscent of the Notre Dame back home, opera theatres for European performances, homes and offices wrapped in stucco swirls and Classical mythological figures, and the omnipresent patisserie producing delectable French pastries.

Hanoi’s oldest church, St. Joseph’s Cathedral, dates to 1886. It was built on the lines of the French Gothic Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris.

![Exuberant stucco embellishments on the facade of Saigon's Central Post Office [1891].](https://ramaarya.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/vietnam-war-colonial-rule-2.jpg)

Exuberant stucco embellishments on the facade of Saigon’s Central Post Office [1891].

Presidential Palace in Hanoi’s Ho Chi Minh Relic Complex was the residence-cum-office of the Governor-General of French Indochina from 1906 to 1945.

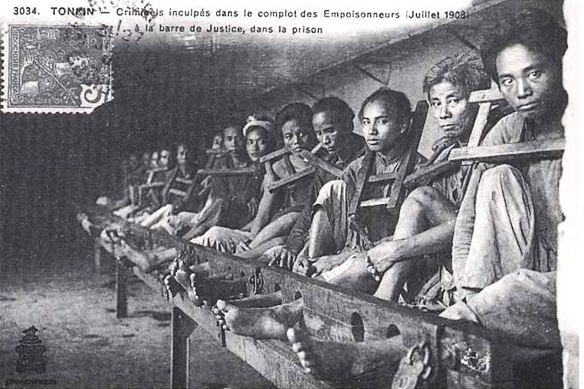

Revolutionaries behind the 1908 Hanoi Poison Plot detained at the Hoa Lo Prison by the French colonists. 13 of them had their heads chopped off instantly and displayed in public. The French later used the photo for an Indochina postcard.

1941.

Whilst the second world war was raging across the world, in Vietnam the Viet Minh Liberation Movement, led by famed revolutionary Ho Chi Minh, was taking birth. Ho Chi Minh had one dream. An independent Vietnam free of foreign rule.

But when World War II ended in 1945, Vietnam split into two. An ‘unrecognized’ communist North Vietnam, known as the Democratic Republic of Vietnam supported by the USSR and China. And a recognized South Vietnam, supported by the French, who were in turn supported by the US and its anti-communist allies.

![Declaration of Independence of Democratic Republic of Vietnam, 2 September 1945. [War Remnants Museum, Ho Chi Minh City]](https://ramaarya.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/vietnam-war-declaration-of-independence.jpg)

Declaration of Independence of Democratic Republic of Vietnam, 2 September 1945. [War Remnants Museum, Ho Chi Minh City]

For nine long years, thereafter, from 1946 to 1954 the First Indochina War ripped across the country. Spilling blood, lives, and peace. On one side were the French. More adamant to stay. More aggressive in their rule. They were helped by the US who provided advisers, funding, and weapons from behind the scenes. Anti-communist Vietnamese loyalists aided the French rulers’ legitimacy. On the other side was Ho Chi Minh and his revolutionaries.

Things eventually came to a head in 1954 with the Geneva Conference and creation of the 17th Parallel, a Demilitarized Zone [DMZ] on 17 degrees latitude north.

Seventy-six kilometres long and around ten kilometres wide, the DMZ, a porous border, divided the country into two—all the way from the coast in the east to the inland border with Laos to the west. To its north, North Vietnam aka the Democratic Republic of Vietnam was declared a sovereign state. The French were told to leave. Within the DMZ itself, there was to be no fighting. Whatsoever.

It was a temporary arrangement, a truce for 300 days, to be followed by General Elections to determine which government would rule a unified Vietnam. The communist government of North Vietnam, or the capitalist government of South Vietnam.

But things do not always go as planned.

The DMZ ended up lasting for 22 years, from 21 July 1954 to 2 July 1976, and in this period was subjected to one of the worst spate of bombings, raids, and war crimes.

Hien Luong Bridge across the Ben Hai river on the DMZ. The bridge has historically been painted half blue and half yellow representing North and South Vietnam.

Memorial of Desire for National Reunification stands to the south of Hien Luong Bridge.

![Union House at DMZ, seat of the International Control Commission [ICC] comprising India, Canada, and Poland. The ICC was responsible for overseeing the implementation of the 1954 Geneva Accords.](https://ramaarya.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/vietnam-war-dmz-3.jpg)

Union House at DMZ, seat of the International Control Commission [ICC] comprising India, Canada, and Poland. The ICC was responsible for overseeing the implementation of the 1954 Geneva Accords.

Flagpole at the northern side of DMZ’s Hien Luong Bridge.

One of the outcomes of the DMZ was Ngo Dinh Diem’s regime in South Vietnam. Prime Minister of South Vietnam when the DMZ was drawn, in 1955 he proclaimed the country Republic of Vietnam and made himself its President. All with the help of the USA.

The latter’s intelligence had revealed 80 percent of Vietnamese were in favour of Ho Chi Minh. Which translated to a communist regime should General Elections take place. Pro-US, autocratic, Catholic, and anti-Buddhist, Diem ensured the UN-mandated elections never happened.

He also liked the good life. His Independence Palace in Saigon came with a night-club and private helipad on the top floor, and bunkers deep in the bowels of the earth under the building.

Meanwhile, a stratum of Vietnamese society who were unhappy with Diem’s rule, and were pro-Ho Chi Minh, decided to go underground in 1961. Literally. Known as the National Liberation Front, the guerilla force functioned from subterranean tunnels and jungle cover. They were determined to overthrow South Vietnam’s Diem government and unify Vietnam under communism. The US called them Viet Cong.

South Vietnam [and the USA] now had two enemies to deal with, and two wars to fight. One against North Vietnam to the north and second, the Viet Cong within its own borders.

Diem may well have got away with everything had it not been for his decision to purge the country of Buddhism, the country’s major religion. He stripped Buddhists of their lands and rights, and had their monks and nuns arrested, who in turn self-immolated themselves in protest. In 1963, faced with a coup, Diem tried to escape from the tunnels under one of his houses [now the Ho Chi Minh City Museum] to the perceived safety of Cha Tam Church in Cholon. Here he was captured and assassinated.

The coup was staged by the USA, the same USA who had brought him to power.

Buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc drove this blue Austin Westminster sedan to Saigon’s city-centre in 1963, where he set himself on fire to protest against Diem’s anti-Buddhist policies. The car now stands in Hue’s Thien Mu Pagoda.

Xa Loi Pagoda in Saigon was a centre of opposition to the Diem-government. In 1963, Diem had his men attack the monastery and arrested its 1,400 monks, nuns, and patriarch.

The USA too, might have continued to stay in the background. Sending money, weapons, and advisors to control the region’s political narrative. Or maybe not.

Their rationale for interfering was simple. To contain communism. They were guided by the ‘Domino Theory,’ that if all of Vietnam fell to communism, so would Laos, Cambodia, and the rest of southeast Asia. This had to be avoided at all costs.

1964.

A purported incident in the Gulf of Tonkin changed the war’s course.

According to the USA, Vietnamese patrol boats had attacked the USS Maddox moored in the Gulf. The US people and congress were enraged at this. Immediately, a resolution was passed to officially engage in war. President LB Johnson, the ‘heart of the war,’ decided to send 500,000 US troops to South Vietnam in 1965 to fight against North Vietnam in the north and the Viet Cong in the south. He called it Operation Rolling Thunder. The campaign would rain 864,000 tons of bombs on North Vietnam over the next three-and-a-half years, killing 52,000 North Vietnamese.

In a 2003 documentary, The Fog of War, the US government admitted that they had fabricated the Gulf of Tonkin incident.

!['Message from Khe Sanh.' [Khe Sanh Combat Base Museum]](https://ramaarya.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/vietnam-war-khe-sanh-combat-base-2.jpg)

‘Message from Khe Sanh.’ [Khe Sanh Combat Base Museum]

Khe Sanh Combat Base was a US Marine Corps military site. In 1968, the North Vietnamese laid siege to it, destroying 78 military vehicles, 197 airplanes, 80 ships, and killing/ capturing 11,900 soldiers. The siege was carried out to divert attention for their upcoming Tet Offensive.

North Vietnam and Viet Cong’s Tet Offensive in 1968 took the South Vietnamese and US forces completely by surprise. Launched on 30 January, on Vietnam’s lunar new year holiday, it was one of the biggest military campaigns in the war.

Cu Chi Tunnels near Ho Chi Minh City played an integral role in this campaign. The 121-kilometre-long network of subterranean tunnels, part of a much larger network that cut across most of the country, were the Viet Cong’s lifeline.

Hidden away under camouflaged booby traps, the tunnels provided the soldiers with supply and communication routes, living quarters, and storage space for food and weapons. Though air and water were scarce, and insects, scorpions, and rodents aplenty, it did not deter them one bit who used the tunnels as hideouts during combat.

Ben Duoc Tunnel in the Cu Chi Tunnels network served as the base for Viet Cong’s Regional Party Committee and Saigon-Gia Dinh Military Command.

Recreated medical facility in the Cu Chi Tunnels in which doctors provided medical treatment to the Viet Cong soldiers wounded in combat.

Left: An American tourist emerging out of a Cu Chi Tunnels entrance; Right: Viet Cong soldiers wore rubber sandals made from discarded tires. Together with a checkered black and white scarf, it formed their ‘uniform.’

![While the US forces and its allies recorded the war using war photographers, North Vietnam and Viet Cong did it through art. 'Sketches of the Southern Resistance War': Ms. Ai Viet, and Night in the Basement. [HCMC Museum of Fine Arts]](https://ramaarya.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/vietnam-war-hcmc-museum-of-fine-arts-1.jpg)

While the US forces and its allies recorded the war using war photographers, North Vietnam and Viet Cong did it through art. ‘Sketches of the Southern Resistance War’: Ms. Ai Viet, and Night in the Basement. [HCMC Museum of Fine Arts]

The US retaliated with the My Lai Massacre on 16 March 1968 in which 504 civilians, mainly women and children, were gang-raped and then mutilated. Those who helped the Vietnamese were seen as traitors. Only one of the US soldiers, William Calley, was later tried; he was sentenced to house arrest for three-and-a-half years.

![My Lai Massacre on 16 March 1968 in which 504 villagers, most of whom were women, the elderly, and children were slaughtered by US forces. [War Remnants Museum, Ho Chi Minh City]](https://ramaarya.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/vietnam-war-my-lai-massacre.jpg)

My Lai Massacre on 16 March 1968 in which 504 villagers, most of whom were women, the elderly, and children were slaughtered by US forces. [War Remnants Museum, Ho Chi Minh City]

The villagers decided to dig by hand a 2-kilometre-long tunnel, 30 metres underground, for safety and survival. The Vinh Moc Tunnels included family rooms, community halls, kitchens, wells, health clinics, and a kindergarten. Some 60 families called it home from 1967 to 1972; 17 children were born inside it. Not a single person from Vinh Moc village died in the war.

Left: Vinh Moc Tunnels were home to 60 families during the six worst years of the war; Right: Kindergarten inside the tunnels.

Built 30 metres below ground-level, Vinh Moc Tunnels had 13 openings of which seven opened out into the East Sea.

Of all the weapons used by the US, the deadliest was Agent Orange, a toxic chemical herbicide and defoliant. They called the campaign which they ran for ten years, from 1962 to 1971, Operation Ranch Hand. Their purpose was to clear Vietnam’s natural forest cover and farms which hid and fed the Viet Cong.

80 million litres were sprayed over 26,000 villages across 3.06 million hectares. Operation Ranch Hand not only defoliated vegetation and crops, but pushed numerous animal species to extinction and caused skin rashes, cancer, and birth-defects down multiple generations in the people who were exposed to the spray on both sides of the battle—the Vietnamese and the Americans.

![Mangrove forest one year after it was destroyed by Agent Orange; its soil still contaminated with the toxic chemical Dioxin. [War Remnants Museum, Ho Chi Minh City]](https://ramaarya.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/vietnam-war-agent-orange-1.jpg)

Mangrove forest one year after it was destroyed by Agent Orange; its soil still contaminated with the toxic chemical Dioxin. [War Remnants Museum, Ho Chi Minh City]

![US forces' gas masks. [War Remnants Museum, Ho Chi Minh City]](https://ramaarya.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/vietnam-war-agent-orange-2.jpg)

US forces’ gas masks. [War Remnants Museum, Ho Chi Minh City]

![Left: 25-year-old Le Thi Thay and her 10-month-old child whose only arm was deformed and the skin beset with rash. Le had been exposed to Agent Orange at age 12; Right: A baby girl born with deformed brain, mouth, ears, and limbs died on the very next day after birth. [War Remnants Museum, Ho Chi Minh City]](https://ramaarya.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/vietnam-war-agent-orange-3.jpg)

Left: 25-year-old Le Thi Thay and her 10-month-old child whose only arm was deformed and the skin beset with rash. Le had been exposed to Agent Orange at age 12; Right: A baby girl born with deformed brain, mouth, ears, and limbs died on the very next day after birth. [War Remnants Museum, Ho Chi Minh City]

Since the DMZ had been transformed into an impregnable war-razed zone, North Vietnam started sending supplies to the Viet Cong through the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a network of foot paths and paved roads astride Laos and Cambodia. When the US forces attacked, they ensured these two bordering nations received the bombs and defoliants as well. Laos, as of date, is the most heavily bombed country in the world.

19th Century Nguyen-era Quang Tri Citadel was the location of intense fighting between North Vietnam and US/ South Vietnam forces during the 1972 Easter Offensive.

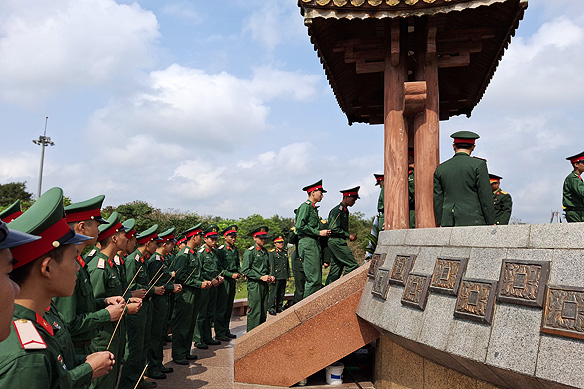

Vietnamese military unit paying homage to those who died in the 1972 Easter Offensive.

By 1972, the US government could see that the war was imploding. After three million dead Vietnamese, and 58,000 dead US soldiers, the victory they had been so confident of was now becoming more and more elusive.

The war had cost America 8,744,000 military personnel serving on active duty with a peak troop strength of 549,500 in 1969, 14.3 million tons of bombs and artillery shells, and USD 676 billion.

Seventeen years and two months of a wasted war, wasted lives, and wasted resources.

Secret negotiations that had started between the US and North Vietnam in 1969 culminated with the Paris Peace Accords on 27 January, 1973 with peace between North and South Vietnam, and peace between North Vietnam and the USA. The peace treaty agreed on a ceasefire, complete withdrawal of US troops, return of POWs, and Vietnam’s reunification.

It would, however, still take another two years for South Vietnam to surrender to the reunification. On 30 April, 1975, North Vietnam finally crashed through the gates of Saigon’s Independence Palace, signalling the city’s fall. That year, 500,000 South Vietnamese refugees immigrated to the US. One year later, on 2 July, 1976, the unified country officially became the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and Saigon became Ho Chi Minh City.

The communist tank which crashed through the gates of Independence Palace on 30 April, 1975, signalling the fall of Saigon and the country’s reunification. Behind it is the Independence Palace, later renamed Reunification Hall.

Underground bunkers with war maps in Independence Palace. South Vietnam, with the help of US forces, strategized the war from these rooms.

1994 was the last landmark year in the American/ Vietnam War story. Vietnam moved from a rigid communist state to an open economy guided by socialism. More importantly, Vietnam and the USA became friends. Good friends, with the US government lifting sanctions and both countries exchanging diplomatic missions.

In 1994, the US also closed its doors to South Vietnamese refugees. There are currently 2.3 million Vietnamese Americans in the US, the fourth largest Asian American ethnic group. Meanwhile, American War Veterans regularly visit Vietnam searching for answers to unasked questions.

Those Vietnamese that stayed back in the country have forgiven and moved on. As one gentle Vietnamese tells me, “I focus on my karma. I try to be good. That is all that matters.”

After-effects of the war live on with birth defects showing up till the 4th generation of those once exposed to Agent Orange. Lang Viet/ Handicapped Handicrafts provide them with a livelihood.

A patch-worked mother-of-pearl horse that will become part of an exquisite lacquered artifact at Lang Viet/ Handicapped Handicrafts’ workshop-cum-showroom.

Travel tip:

- I explored most of the sites mentioned in this post on my own as I travelled through the country from south to north over three weeks. For the DMZ, I did a day tour from Hue with Connect Travel. Their guide Hoa was more than brilliant! One of the best I have ever come across.

– – –

With this post, I also come to the end of my Vietnam series. In case you missed any of my earlier posts on Vietnam, here they all are.

Thank you for accompanying me on my travels through Vietnam. ❤

PS: If you enjoyed this post, you may also like to read these:

Secrets of USSR’s Polygon nuclear test site

Cambodia: The sacred and ugly of divine rule

Hebron, half-brothers of a common father: Microcosm of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

Global travel shot: Remembering Auschwitz

Photo essay: In search of Kandahar, the Taliban’s former capital

!['The Soldier of all Ethnicities' by Le Thu Thao [Age 8], Crayon on paper. [War Remnants Museum, Ho Chi Minh City]](https://ramaarya.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/vietnam-war-childrens-painting.jpg)

‘The Soldier of all Ethnicities’ by Le Thu Thao [Age 8], Crayon on paper. [War Remnants Museum, Ho Chi Minh City]

Thanks Rama for an objective account and pictures of terrible times. A couple more recommendations of novels which I read a long time ago from both sides which are in may ways quite similar in their portrayal of the effects of the horror on the combatants – ‘The Things They Carried’ (1990) by Tim O’Brien and ‘The Sorrow of War’ (1991) by Bao Ninh. And now as a tourist experience you can crawl through the Cu Chi Tunnels (which I did) and fire an AK47 (which I didn’t). Weird ….

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the recommendations. Appreciated. Am glad you found the post objective. Everyone suffered in this war, in some way or the other. War is never the answer. Ever.

LikeLike

An impressively comprehensive overview.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for your kind words, Mitch. I really believe some countries cannot be understood without their political contexts. These political histories permeate across their present, shaping their societies, values, and behaviours. And their monuments and art. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I remember feeling so depressed and saddened after visiting the War Remnants Museum. It’s crazy to think of the amount of bombardment Vietnam received. As much as South Vietnam modelled itself after Western democracies, what I learned is that its government was deeply unpopular among the population.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It is a heart-wrenching place. So much suffering. Yes, the South Vietnam governments were unpopular, especially Diem’s. Travelling through the country, Vietnam’s history kept piling inside my head, and the archival images collecting in my camera. I knew I had to write one post just on the war. This post is actually for me. So that I do not forget what I learnt. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person