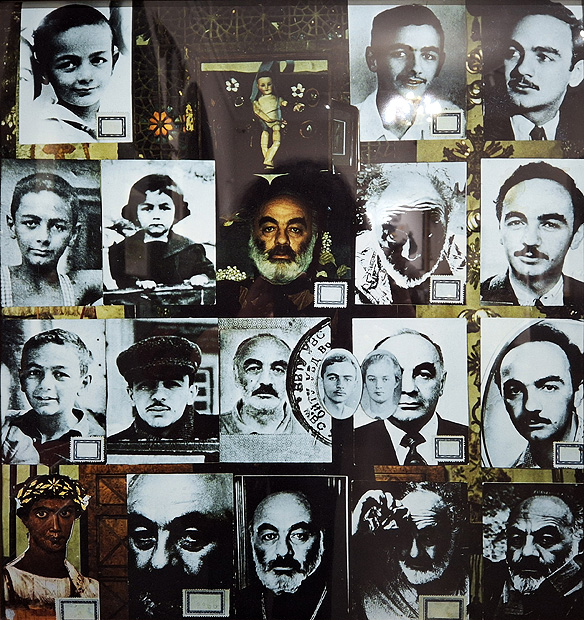

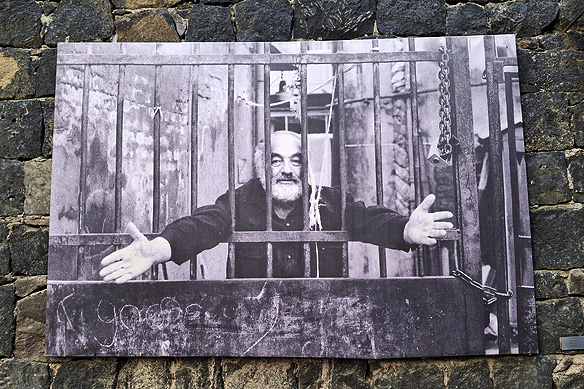

I Am 60 Years Old, 1984.

When one’s life pans out like a movie, can one’s art be far behind?

Described as a magician in the world of cinema, Sergey Parajanov’s movies stand out for their tableaux sheathed in visual poetry. There are no clearly defined narratives or dialogues in the four globally acclaimed films he made in his lifetime. Instead, in its place are near-static scenes lush with colour and symbolism which explore the stories within us rather than outside of us.

Born to Armenian parents in Tbilisi in 1924, Parajanov’s first love was a Tatar Muslim woman Nigyar Kerimova. Soon after their marriage in 1951 she was murdered by her brother for marrying a Christian and converting to Christian Orthodoxy. When 32, Parajanov fell in love with 17-year-old Ukrainian Svetlana Sherbatiuk. The marriage ended in divorce.

Unlucky in love, but lucky in life? It was not to be so with Parajanov. Fame merely brought him more misery. His refusal to conform to Soviet Union ideals and the Socialist Realism style led him to being imprisoned twice. The second time around, when released, it was on condition that he be forbidden from living in Moscow, Leningrad [St. Petersburg], Kiev or Yerevan, nor be allowed to make films. The ban lasted for 15 years.

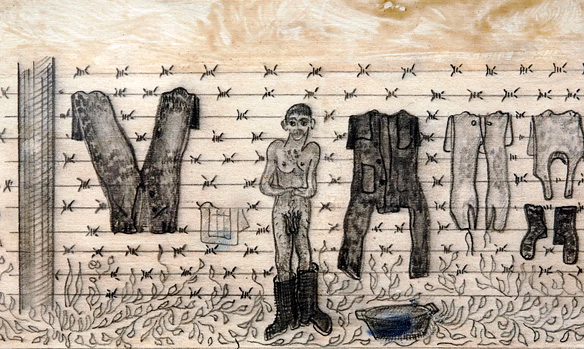

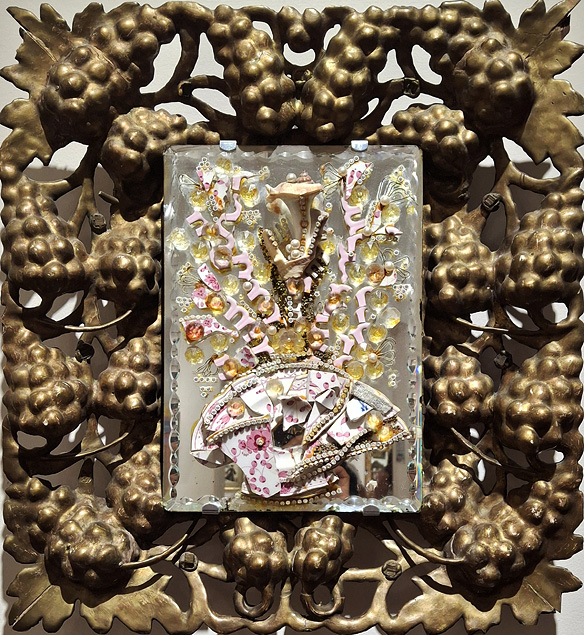

Bereft of the freedom to create films, it was in the dark squalor and aching hunger of the gulag camps that he turned to making collages. He described his collages as ‘compressed films.’ The most poignant are his seemingly simple boxed dolls which hold lifetimes in their narratives, made from pieces of sack he would pick up whilst doing manual labour.

Another product of his gulag days is the series on Golconda’s life, a collection of collages with Mona Lisa as the central figure in which she alternates between smiling, frowning, crying, and laughing.

Parajanov said, “Once, when it was very hot, we took our shirts off and worked bare-chested, and I saw a tattoo of the Gioconda on an inmate’s back. When he lifted his arms, his skin would stretch and Gioconda smiled, when he leaned forward, she became gloomy, and when he scratched behind his ear, she smirked. She kept making faces!” Perhaps it was these memories which led to the creation of the series.

His collages, which took birth during his incarceration, were to become an art form he would carry into his freedom. During his lifetime, Parajanov made over a thousand collages, dolls, hats, and drawings.

Though better known as the creative giant behind masterpieces such as Shadows of the Forgotten Ancestors [1964] and The Colour of Pomegranates [1969], his collages were just as much a part of his surreal creativity. He was a visualist—his collages a lesson on how an entire story can be compressed into a single frame.

Parajanov never got to live in his house museum in Yerevan where his collages, sketches, and personal belongings have been on display since 1991. The exhibits include six thalers. While in the prison’s isolation ward, he used his fingernails to emboss aluminium bottle caps. A silver replica of one of the thalers is given as a lifetime achievement prize at the Golden Apricot International Film Festival held in Yerevan since 2004.

Aged 66, Parajanov died of lung cancer in 1990. Before dying he was given permission to make two films. The award-winning The Legend of Suram Fortress [1985] and Ashik Kerib [1988].

The house museum was his dream, which like many in his life, ended up being curtailed. At times he was in the wrong place. At times, the timing was wrong. But his art, aah, that was always right.

![My First Automobile [Photo 1927].](https://ramaarya.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/sergey-parajanov-6.jpg)

My First Automobile [Photo 1927].

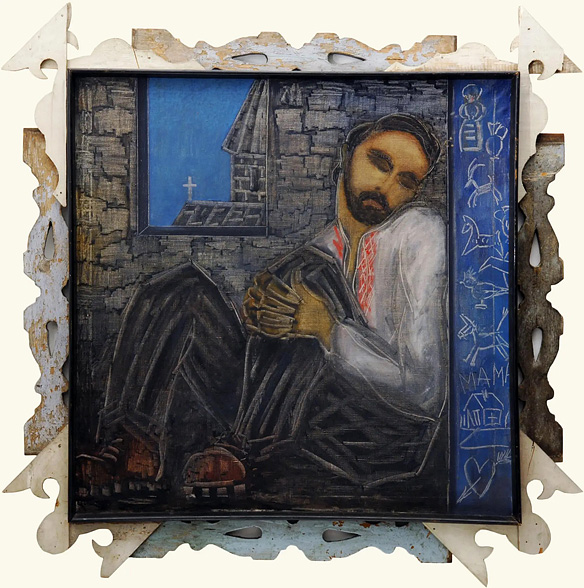

Self-Portrait Against the Background of Haghpat, 1963, Courtesy Sergey Parajanov Museum, Yerevan.

Barber Zhora, My Brother-in-Law, 1969.

Shower Day in Prison, 1974-1977, Courtesy Sergey Parajanov Museum, Yerevan.

Thalers, 1975-1977, Courtesy Sergey Parajanov Museum, Yerevan.

Left: Weeping Gioconda, 1977; Right: Coat-of-Arms of British Admiralty, 1984.

Red-Finned Fish, 1981.

Dodo is Pinching Cigarettes, 1982, Courtesy Sergey Parajanov Museum, Yerevan.

Life and Death of General Radko, 1983, Courtesy Sergey Parajanov Museum, Yerevan.

Elections at the Marionettes, 1984.

Left: Retro, 1984; Right: Ferdinand in Franz-Joseph’s Stable, 1984.

Danaya, 1984.

The Destiny of Woman, 1985.

Romulus and Remus with Accessories, 1986.

Bouquet to My Missing Cousin, 1986.

Bouquet after Rain, 1987.

Variation with a Shell on Themes by Pinturicchio and Raphael, 1988, Courtesy Sergey Parajanov Museum, Yerevan.

– – –

Travel tips:

- The Sergey Parajanov Museum has an audio guide with an interesting 30-minute narrative on Parajanov’s life and work. Entry ticket: AMD 1,500; Audio guide: AMD 2,000.

- Try and watch Parajanov’s film ‘The Colour of Pomegranates’ before your visit [link in text above] to understand his distinctive style.

[Note: I travelled solo and independently across Armenia for 12 days in September-October, 2025.]

Bizarre, but wonderful

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I felt the same way about his work. Quite unlike anything I have seen to date. 🙂

LikeLike

Wow the works are intense and so expressive. What stands out is the amazing desire to create something and express himself even when in the most dreadful of circumstances. Its so good to see that it has not been lost and forgotten as we live in a world of 5 minute TikTok trash

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed, the desire to create and express under any circumstances. His collages are so personal. I really enjoyed the museum. One of Yerevan’s absolute gems. 🙂

LikeLike

Clarity and depth harmonized

LikeLike

Thank you. 🙏

LikeLike

Pingback: from a 5,500-year-old shoe to genocide to fountains: 72 hours in yerevan | rama toshi arya's blog