Buddha statue in Langza Village. Because the gods live in the mountains.

Welcome to part 2 of my photo diary trilogy on Kinnaur, Spiti, and Lahaul.

This week’s post is about Spiti, a cold desert biosphere in the rain shadow area of the Himalayas bordering Tibet. India’s monsoons do not reach here. Even if they do manage to squeeze their way past the soaring peaks, all they are able to muster is a drizzle. The summers are always dry. The winters are covered in thick snow and ice.

None of which is conducive to agriculture except if carried out on the banks of the Spiti river. The land is otherwise brown and barren, its moonscapes strewn with sand and boulders. Nestled in this arid bleakness are countless ancient monasteries, bedecked and bejewelled with Tibetan Tantric Buddhist iconography. These pockets of sanctity serve as places of refuge, giving strength and meaning beyond a difficult life.

Come along with me to Spiti. ❤

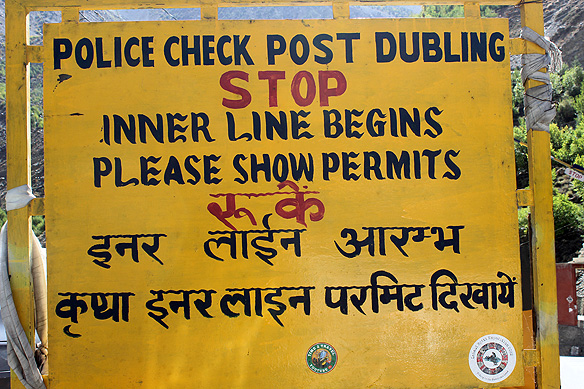

Since Spiti adjoins the country’s border, foreigners need special permits to enter the valley. Indian citizens, however, only need to show their identity cards.

What’s a visit to Himachal Pradesh without a bowl of veg maggi from a street-side stall. This was lunch at the dhaba by the Khab bridge. The bridge spans the confluence of the Sutlej and Spiti rivers.

Ka-loops’ hairpin bends en-route to Nako.

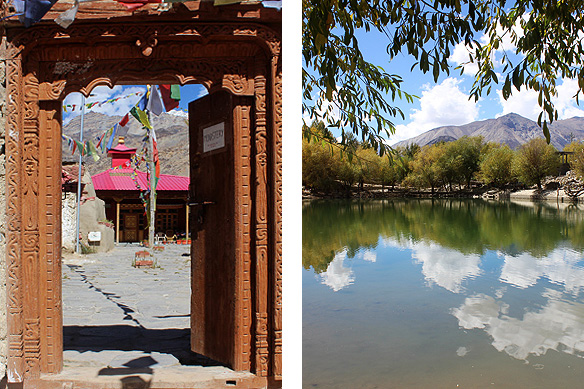

Nako, one of the highest villages in Upper Kinnaur facing Tibet, is where the Kinnaur valley ends and the Spiti valley begins. With just some 500 people calling it home, it comprises of a monastery originally built in 1025 and restored post the 1975 earthquake, and a man-made lake lined with willow trees and prayer flags. There are no doctors, no electricity, no internet. Welcome to the high mountains of the Himalayas. 🙂

Picture postcard Spiti.

Tabo is all magic! Pure Tibetan Tantric Buddhism magic. The holiest and oldest continuously operating monastery in India, it was built in the year 996 and is often described as the ‘Ajanta of the Himalayas.’ Reason? Inside the nine mud temples is an overload of ancient thangkas, manuscripts, effigies, and murals. Unfortunately, photography is not allowed.

There is another feature which sets the monastery apart from others. Instead of being perched high up on a mountain summit, Tabo, designed as a fort, lies on the banks of the Spiti river surrounded by apple orchards planted by the monks.

India’s only ‘mummy’ sits in a small room in Gue Village near Tabo and the Indo-Tibetan border. Meet Sangha Tenzin, a lama who decided to preserve his body naturally 500 years ago. He first starved himself, then ate poisonous nuts, and finally ran lit candles along his skin to dry it out.

He was forgotten to the world right until 1975. After the earthquake exposed his tomb the Border Police housed him in a small temple where the likes of tourists and pilgrims drop by to say hello.

Part of the Langza-Hikkim-Komic circuit, the highly atmospheric Tangyud Monastery in Komic is a relatively new structure—1975. The original edifice used to be in Hikkim, but was destroyed in the Spiti earthquake. What it lacks in historical significance, the monastery more than makes up for in location. High up at 4,587 metres, I felt on top of the world, literally, with 360-degree views for hundreds of miles. What is a view without a meal, do I hear you say? Next to the monastery is the world’s highest organic restaurant.

No trip to Spiti is deemed complete without a postcard sent from the world’s highest built-up post office in Hikkim set up in 1983 by the local postmaster. Sans any internet or phone connectivity, it is the only way the village, and those around it, stay connected to the rest of the world. When winter falls, the post office shuts its services till next year’s spring.

Nearby is the Langza Village with its monumental statue of Buddha. Popularly known as Fossil Village, the whole area once lay under the prehistoric Tethys Ocean. When the tectonic plates collided, these rolling highlands rose up 4,420 metres to become part of the Himalayas, the roof of the world. The earth here is filled with marine fossils. Though often sold, may I request you do not buy or pick up any. Let them stay where they belong so that others can also enjoy their million-year-old stories.

The very symbol of Spiti culture and the valley’s most famous monastery is also its largest, one of the oldest, and a centre for learning. Established in the 11th Century by the founder of the Tibetan Gelugpa sect, the Ki Monastery is where the region’s lamas have historically been trained. Attacked and rebuilt many times over, it is high up in the Himalayas at 4,166 metres …

… My eyes were, however, on the peak overlooking the monastery—Tashigang, covered with a mass of windswept prayer flags—which a dirt road took me to under a powder-blue sky.

Chicham, Asia’s highest suspension bridge towers over a 100-metre-deep gorge. Before it was built in 2017, the only way to get to the villages on the other side was by a pulley and ropeway system. Together with Spiti’s other roads and bridges, it was built and is maintained by the Border Roads Organisation, a part of the Indian government’s Ministry of Defence.

Dhangkar, my destination, literally means Fort on the Cliff. ‘Dhang’ is Tibetan for cliff, in this case one at a height of 3,894 metres, and ‘Kar’ is fort. Capital of the 17th Century Nono rulers of Spiti, its main claim to fame today is its crumbling 12th century monastery, and the ruins of a mud brick fort. At one time the entire town’s population lived within its fortified walls overlooking the confluence of the Pin and Spiti rivers, and protected themselves by throwing stones at invaders.

I met one of the monks inside the old monastery who gave me a cup of seabuckthorn tea and let me poke around the shadowy rooms. He was the second son in his family; his parents had ‘given’ him to the sangha [Buddhist monastic order] when he was a child. It is a practice that still prevails. I asked him if he was happy being a monk. He told me that for the longest time he had envied his elder brother for having a wife and family, a home, a career. He would ask himself why not him. His own whole life had been spent inside the monastery walls. But he was okay with it now. He had made peace with a destiny he had never had a say in, and could never change.

Acceptance. I sipped my tea in the dark windowless chamber lit by yak butter lamps, the word reverberating inside of me.

One of my homestays was in Lalung. Lalung means God’s Land. I had a pretty room overlooking the mountains and my host was a lovely lady whose husband cooked delicious meals. Before tucking in for the night, I decided to take a stroll through the village until I was chased away by a large black hairy yak returning home, and a 5-year-old had to chase the yak away for me.

As always, it was subzero at night. The solar lights had died out as well. The following morning, after dousing myself in deo, I apologised to my host for not bathing. She laughed out aloud. “No-one bathes here every day. Once winter falls, the pipes will freeze. If there is water to cook, that is a blessing. By the way, do not forget to visit the monastery. I will tell the lama to meet you there with the key.”

Lalung Monastery is one of those jewelled pockets which Spiti is packed with and has a fantastical tale of its own to boot. Gilded and painted, its dark rooms are said to have miraculously cropped up in the 10th Century, next to a seabuckthorn tree that the village’s spiritual leader had given to the villagers. The tree still grows in the monastery complex.

On to Pin valley which was declared a wildlife reserve in 1987. It is renowned for its snow leopards and Siberian ibex which are best sighted when the area is blanketed under many feet of snow. On an autumn morning, this was what it looked like.

Just a slightly rickety handmade suspension bridge across the Pin river that I decided to take a stroll on.

Spiti’s second oldest functioning monastery is in Kungri Village and dates to 1330. I found myself to be in time for a chanting session carried out by monks, nuns, and novices—the whole commune—as part of a religious event’s grand finale. What a performance it turned out to be, replete with traditional drums and trumpets accompanying sonorous sacred mantras.

And back again to Kaza.

At 3,800 metres, Kaza, Spiti’s commercial centre and base for exploring the region is higher than even Leh [3,500 metres]. The old town, Kaza Khas, is criss-crossed with narrow crowded lanes, souvenir shops, and quaint cafes serving piping hot thupkas and seabuckthorn tea, with bikers in black leather revving in and out loudly. In Kaza Soma, the new town, is the Eight Stupas and the bright and colourful Tangyud Monastery [2009]; the latter rarely visited by tourists.

– – –

I hope you enjoyed the above virtual tour of Spiti and are tempted to explore it in person, someday soon. Next week I will be writing about Lahaul, the third and final part of the trilogy. Wishing you happy travels. Always.

[Note: This blog post is part of a series from my 15-day solo road trip to Kinnaur, Spiti, and Lahaul in Himachal Pradesh. To read more posts on my Himachal Pradesh travels, click here.]

How people manage to grow food and live and work and create such monumental and colourful places of worship in such arid, harsh and seemingly waterless surroundings is beyond my comprehension. It seems miraculous. Sublime and beautiful and today (hopefully) peaceful. The mummified man looks as if he’s just about to say something or is it surprise at being approached. What an amazing set of pictures and text – thanks once again Rama for raising the spirits in an increasingly violent and disintegrating world.

LikeLike

A great tour through Spiti and its arid landscape coloured only by the Tibetan monasteries. I’d love to some seabuckthorn tea or juice again. We didn’t know of the mummy in Gue, otherwise we may have gone. Maggie

LikeLike

Its such a beautiful landscape but must be so harsh in the peak of winter. Thanks for sharing this region with me!

LikeLike

Super photos again – a great place!

LikeLike

Yet another reminder of why I fell in love with the Himalayan regions. Your photos of those monasteries in Spiti are enough to make even the most jaded travelers think of going on a trip to this part of the world. And thank you for advising us not to buy or pick up any marine fossils. I always believe that things like these are much better kept at their original locations.

LikeLike