Delhi, a city of 7 cities, 8 cities or 14 cities? It depends on which lens one is looking at the city from. But it surely is not one city!

India’s political centre has been around for a long time. 1,300 years as per historical records, in which it served as the capital city for different rulers over various periods.

Many set up their own capital, in their own name, for posterity’s sake in and around Delhi. For instance, Mubarak Shah, the second Sayyid dynasty ruler during the Delhi Sultanate period founded Mubarakabad in the 15th Century [included in the 14 cities list]; it is now a neighbourhood called Kotla Mubarakpur.

All together, 14 such cities were built over the centuries in this patch of strategically placed land in northern India with the fertile Gangetic plain to its east, the impenetrable Deccan plateau to the south, and the arid desert state of Rajasthan to the west. An area nourished by the river Yamuna and the monsoons.

Much smaller than present-day Delhi, these cities were often built a short distance away from an old one or incorporated earlier ones into its boundary walls, and at times even existed concurrently. Each of them has added a distinctive layer to Delhi, making Modern India’s capital quintessentially different from any other. Where else can you time travel across a millennium in an hour.

For this post, I am taking the ‘8 cities in a city’ theory. Seven historical cities in Delhi that still exist, and New Delhi, listed in chronological order.

It is a longish post. After all, we talking about 1,300 years and eight cities. 🙂 Hope you enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed writing it.

Happy time travel!

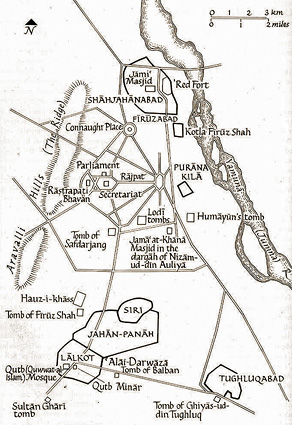

PS. If you would like to know about all 14 cities, here’s an interesting article on them by author and historian Rana Safvi. I have also included a map of Delhi’s eight cities at the end, to help you locate the ones mentioned in this post.

1. LAL KOT AND QILA RAI PITHORA: DELHI’S FIRST CITY

The walls of Lal Kot in Sanjay Van trace themselves back to the Tomar rulers of the mid-11th Century. It is within these same walls that the Delhi Sultanate’s first city came up.

Qutub Minar complex, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and the birth-place of Indo-Islamic architecture that is unique to India.

Battle of Tarain II. The year—1192.

It was 460 years since the Rajput ruler Anangpal I had built the city walls of Lal Kot in 731 AD. City walls that were extended by a descendent, Anangpal II, three hundred years later, and even further by Prithviraj Chauhan III who renamed it after himself: Qila Rai Pithora. A city decorated with 27 intricately decorated Hindu and Jain temples placed around a 4th Century AD iron pillar brought all the way from Udaygiri. Prithviraj Chauhan III would stop here to pray whenever he was in town.

Northern India was no stranger to invasions by Central Asian Turkic rulers. But whilst Mahmud of Ghazni was happy to raid and leave with his plunder in the early-11th Century, Muhammad Ghori who led the battle in 1192, wanted to stay. He wanted to create a new empire across the Indus River, in the land known as Hindustan.

After defeating Prithviraj Chauhan III, the last Hindu king to sit on Delhi’s throne, Muhammad Ghori left behind his trusted ‘slave-general’ Qutub ud-Din Aibak to look after the new territories.

And India was never to be the same again. Seven centuries of Islamic rule and Delhi as an Islamic centre, had been set in motion.

The first of five unrelated dynasties to rule the Delhi Sultanate, the Mamluk or Slave dynasty was in power till 1290. Its founder, Qutub ud-Din Aibak was quick to set up grand structures in the existing Qila Rai Pithora to announce their takeover: Structures that were Central Asian in design and created by Indian craftsmen.

Qutub Minar, a gigantic victory tower, Quwwat al-Islam Masjid, a cut-paste congregational mosque using building material from the existing Hindu and Jain temples, and huge screens pointing towards Mecca were erected. His successor, Iltutmish added his tomb, and extended both the victory tower and the mosque.

Later, Alauddin Khilji, of the Khilji dynasty, added a madrasa, his tomb, grand doorways [of which only one remains, the Alai Darwaza], and had plans to build a victory tower, the Alai Minar, twice the size of Qutub Minar.

So enamoured were Delhi’s later rulers with its first city, they continued to renovate and maintain it, even after creating their own new cities.

NOTE:

You may also like to read The Story of Qutub Minar

Travel diaries: From Bamyan to Herat via the Minaret of Jam

2. SIRI: A CITY BUILT OVER 8,000 SEVERED HEADS

The mandatory heritage walk group picture at the Lodi-era tomb of the Sufi saint Hazrat Makhdoom Sabzwari [left]. The right image is of Muhammadwali Mosque.

Chor Minar in Hauz Khas, built by Alauddin Khilji, served as a deterrent to both enemies and thieves.

Left: Tughlaq-era Mallu Iqbal Khan’s Eidgah; Right: Tohfewala Masjid, the only other monument apart from Chor Minar that is attributed to Alauddin Khilji.

Some cities are built on foundations of brick and mortar, and then there are those built on severed heads. Siri, which is derived from the word ‘Sir’ meaning ‘head’ contains the sliced-off heads of 8,000 Mongols defeated by Sultan Alauddin Khilji in 1303. Or so, popular belief claims.

Siri, though, is a later name. Alauddin Khilji, who belonged to the second dynasty which ruled during the Delhi Sultanate, called his city Dar-ul-Khilafat or Seat of the Caliphate.

If Delhi could stave off the Mongol rampage through Asia, it was essentially because of Alauddin Khilji. After the 1303 attack, he built a large oval-shaped city hemmed in by towering impregnable double walls fed by uninterrupted water supply from the Hauz-e-Alai [now Hauz Khas lake]. For further security he set up a string of forts on the Mongol route all the way to Kabul.

Alauddin Khilji was a complex man. He had his uncle/ father-in-law murdered in 1296 so he could become Sultan, imposed a 50 percent agriculture tax to fund his military exploits, imposed price control mechanisms to control inflation, saw himself as a world ruler, the 2nd Alexander, and was openly bisexual.

His 20-year reign was marked with stability and oppression; around half the city’s population comprised of slaves—either from war or not having paid taxes.

Not much remains of Siri today.

Almost all of Alauddin Khilji’s city, including the Hazar Sutun or Thousand Pillars Palace, ended up being used as building blocks by Sher Shah Suri in the 16th Century for his own capital Shergarh near the Old Fort. Except for a poetic mosque called Tohfewala Masjid in Shahpur Jat and Chor Minar in Hauz Khas. The latter, pierced with 225 holes was used to hang the decapitated heads of the leaders amongst the 8,000 defeated Mongol soldiers. Thereafter, it displayed heads of criminals as a deterrent to thieves.

Until Sher Shah Suri stripped Siri apart, it continued to be used by the later Delhi Sultanate dynasties, namely, the Tughlaqs, Sayyids, and Lodis. Evocative of those years are the Tughlaq-era nobleman Mallu Iqbal Khan’s monumental Eidgah [1405], and the Lodi-era [1451 – 1526] tomb of the Sufi saint Hazrat Makhdoom Sabzwari and Muhammadwali Mosque.

3. TUGHLAQABAD: THE CITY CURSED BY A SAINT

The ruins of Tughlaqabad are best explored during the monsoons when they are blanketed by lush green cover.

Tomb of Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq, founder of the Tughlaq dynasty and Tughlaqabad. He lies buried inside with his wife and the son who murdered him.

Massive, abandoned, and frozen in time, Tughlaqabad holds the distinction of being Delhi’s only city which has never been built over.

Founded in 1320 by Sultan Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq, the founder of the Tughlaq dynasty, it was abandoned in 1325, five years later. All because of the curse of a local saint he happened to rub the wrong way.

Ghiyasuddin was not the Sultan’s real name. It was his title, meaning Supporter of Religion, in tandem with the directive given to him when placed on the throne by the Turkic nobility in control of political affairs in Delhi. With Alauddin Khilji’s death and the murder of his children, Islam was seen to be in danger.

Prior to becoming Sultan, Ghiyasuddin had been a commander in the Khilji dynasty’s army, and had spent most of his life in Multan fighting the Mongols. This translated into a new heavily fortified self-contained imperial city perched on Delhi’s craggy Aravalli hills, its 6.5 kilometres of perimeter punctuated with 13 gates.

Tughlaqabad was replete with multi-tiered thick sloping fortifications rising to a height of 25 metres at places, impregnable bastions, large granaries and water reservoirs, subterranean storage rooms for ammunition and treasures, and a pavilion called Jahanuma, meaning World-View, atop the compact unadorned citadel Burj Mandal on a hillock.

All was fine, except there was a clash of egos throughout his rule with the local Sufi saint Nizamuddin Auliya. Reason? It started off with the Sultan asking the saint to return a grant he’d received from the previous rulers and culminated in whose edifice should the labourers work on first. The new city or the saint’s stepwell. The stepwell won, along with a curse by the saint:

“Ya basse gujjar, ya rahe ujjar!”

[Tughlaqabad will either be occupied by nomads or be forever barren]

When Ghiyasuddin was assassinated by his son Muhammed Bin Tughlaq in 1325 under the pretext of an invitation to a celebration, the city was left to waste.

Maybe the curse worked. Or maybe it ran out of water as historians claim. Or perhaps the son felt a wee bit guilty living in the same house of the parent he had murdered. The irony is, he was later buried right next to him in the Tomb adjoining Tughlaqabad Fort.

4. JAHANPANAH: A ‘MAD GENIUS’ SULTAN’S ‘REFUGE OF THE WORLD’

Bijay Mandal [palace area] and Begumpur Masjid [congregational mosque] of Jahanpanah, the largest city in the Islamic East in the early-14th Century.

Satpula Bridge, named after its sat [seven] water tunnels, was a fortified bridge-cum-dam complete with bastions.

Countless Sufi shrines were built across Jahanpanah over the centuries. One such, Hazrat Sheikh Yusuf Qattal’s Dargah, continues to be revered.

“The king was freed from his people and they from their king.”

This one single quote by Badauni, a 16th Century historian on the death of Sultan Muhammad Bin Tughlaq in 1351, sums up the ruler and his reign.

Shortly after killing his father in 1325 to acquire the throne, Muhammad Bin Tughlaq moved out from Tughlaqabad and established his new capital Jahanpanah, meaning Refuge of the World.

It enclosed two older capitals, Siri and Lal Kot/ Qila Rai Pithora and the area in-between, in thick fortified walls. Bijay Mandal, the palace, housed treasure pits filled with precious stones and gold coins, and Hazar Sutun, an audience hall with 1,000 pillars where he meted out his macabre version of justice.

Muhammad Bin Tughlaq was a man of epic contrasts. A devout follower of the Sufi saint Nizamuddin Auliya, on one hand he was a poet, calligrapher, scholar, and an art lover. On the other, he administered extreme cruelty without blinking an eyelid. He was an expert in infrastructure and town-planning. But, constantly came up with bizarre ideas which shook the very fabric of his empire.

For instance, immediately after establishing Jahanpanah he shifted his entire populace to the Deccan in 1327 to set up a new city Daulatabad, and then back to Jahanpanah again in 1334 to resist Mongol invasions! If that was not enough, he came up with token money which ended up emptying the royal coffers, and leading an expedition against the Mongols only to give up halfway in Kashmir.

Despite all the chaos, true to its name, Jahanpanah, the largest city in the Islamic East at its time did emerge as a refuge.

Innovative irrigation systems, such as the Satpula Bridge ensured plentiful water supply and its strong walls promised safety. Even after the Sultan’s death, majestic mosques such as Khirki Masjid and Begumpur Masjid, by the father-son Wazir duo from Telangana, were constructed, and the city remained a haven for Sufi saints.

5. FIROZ SHAH KOTLA: FOUR DECADES OF PEACE AND CONSTRUCTION

When Timur [Tamerlane] attacked Delhi in 1398, he was so impressed by Firoz Shah Kotla’s mosque, he first prayed in it before destroying it, and then took Indian artisans back with him to Samarkand to create a similar one.

A 3rd Century BC Ashokan pillar, which finds its way from Haryana to the citadel, and Delhi’s only circular stepwell, both courtesy Sultan Firoz Shah Tughlaq.

Delhi’s 5th city, Firozabad, was a trailblazer. Spread along most of present-day Delhi’s length, it was the first to be built on the banks of River Yamuna. Its citadel was the first to be demarcated into purpose-specific sections, setting a prototype for the Mughals. And it was built by Medieval India’s first conservationist: Sultan Firoz Shah Tughlaq.

Firoz Shah Tughlaq was a reluctant Sultan and an orthodox bigot of sorts. He was 42 and happily about to denounce earthly pleasures, on his way to Mecca for Hajj, when he was placed on the throne by the Council of Nobles in 1351.

The very antithesis of Muhammad Bin Tughlaq, his predecessor and cousin, he was everything Muhammad was not. Calm, gentle, unambitious, averse to shedding Muslim blood, with focussed passions, namely, building and conservation, hunting and elephants. He raised salaries, waived off loans, and even had a department for charity, Diwan e-Khairat.

His reign till 1388 was a period of stability and peace, during which he founded six cities and built an unprecedented number of public works. Whilst most rulers were keen to destroy earlier structures, he repaired and conserved many, including the Mamluk dynasty Qutub Minar and Khilji dynasty Hauz Khas.

Most of Firozabad was scavenged 250 years later to build Shahjahanabad, Delhi’s 7th city, but his citadel, Kushk-i-Firuz, still stands—an eclectic collection of edifices. These range from a 13-metre-high, 27-tonne 3rd Century BC Ashokan Pillar he brought in from Haryana and placed on a custom-built 3-storey structure, one of Medieval India’s most beautiful congregation mosques, and Delhi’s only circular baoli [stepwell]. Interspersed amongst these were palaces and guard houses.

A befitting ensemble put up by a ruler who saw building and conservation as a service to both god and his subjects. To make sure future generations remembered these achievements, he put up a domed canopy inside the mosque and inscribed it with the Futuhat-e-Firoz Shahi, a list of his works.

His very nature, however, was to be his bane. Ten years after his death, in 1398, his unarmed city was sacked and its people massacred by the ruthless Turkic-Mongol Tamerlane.

6. DINPANAH AKA SHERGARH: THE CAPITAL OF TWO OPPOSING STALWARTS

Till the 1900s, Bada Darwaza, the only gate by which one can now enter the Fort, was accessed by a drawbridge across a moat.

Sher Shah Suri’s architectural gems: Sher Mandal [1541], an observatory, and Qila-i-Kuhna Masjid [1542], one of Delhi’s most beautiful mosques.

Left: The Tomb of Bedil in nearby Bagh-e-Bedil houses Tajikistan’s 17th-18th Century philosopher-poet; Right: Unusual leoglyphs embellish the Fort’s Talaaqi Darwaza or Forbidden Gate.

It was the year 1530. Humayun, a gentle 23-year-old prince, had been catapulted to the Mughal throne when his father Babur, the founder of the Mughal empire, died just four years after defeating the Delhi Sultanate.

After consultation with the wise and pious, Humayun earmarked a site for his capital. It was to be where once Indraprastha, the legendary city of the Pandavas in the Mahabharata stood. The new capital would be called Dinpanah: Refuge of the Faith.

Till 1556, this new city teetered between opposing factions changing names from Dinpanah to Shergarh, and back to Dinpanah again, only to be eventually abandoned and called Qila-i-Kuhna or Purana Qila [Old Fort]. But not before destiny-changing decisions were made within its walls and a political and administrative legacy created which would survive centuries.

It all started with Humayun being forced to ward off competing siblings and chieftains in order to keep the fledgling empire intact. He was eventually ousted from his throne after ten years by Sher Shah Suri, an Afghan noble from Bengal.

Sher Shah Suri was ambitious and intelligent, managing to achieve remarkable things in his short five-year-reign such as expand the Great Trunk Road, develop an extensive postal system, and introduce the Rupaiya or Rupee, India’s currency.

Instead of creating a new capital, Sher Shah Suri figured it would be more prudent to just renovate Dinpanah and call it Shergarh. So, he destroyed Humayun’s buildings and put up Qila-i-Kuhna Masjid, an exquisite mosque, and Sher Mandal, an observatory, amongst others. Shergarh’s city extended beyond the Fort, entered by Lal Darwaza.

Humayun, nonetheless, was made of more resilient stuff. He re-entered the Indian subcontinent 15 years later, in 1555, with a massive army courtesy of the Persian ruler Tahmasp I, took over Shergarh and turned it back into Dinpanah, ensuring Mughal rule for the next 300 years.

Barely six months into his second tenure, Humayun, an avid astronomer and astrologer, tripped on the steep stone steps of Sher Mandal as he was about to kneel to pray, and died. His son Akbar, thereafter, moved to Agra. Dinpanah’s mandates had been accomplished.

NOTE:

You may like to read about another Delhi monument associated with Mughal Emperor Humayun: Humayun’s Tomb: An Ode to Destiny’s Child.

7. SHAHJAHANABAD: WHEN THE MUGHAL EMPIRE WAS AT ITS ZENITH

Qila e-Mubarak, the Blessed Fort: Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan’s residence-cum-office in Shahjahanabad.

Facades of bygone eras still line the narrow lanes of Delhi’s 7th city.

Left: Jama Masjid was the biggest mosque in India when it was built in 1656; Right: Jain Naya Mandir, naya [new] only in name; it dates back to 1807.

The Mughal empire was at its cultural and artistic zenith when Emperor Shah Jahan decided to move his capital from Agra to Delhi in 1639. Back to where his great-grandfather Humayun had ruled the empire from. No, not to Dinpanah. He intended to create a brand-new city for himself near it, also along the banks of the Yamuna River, and call it Shahjahanabad.

Shah Jahan was an architect and an aesthete par excellence. Under his patronage, pietra dura [an Italian technique adopted by the Mughals] reached an unprecedented finesse in its delicacy, stone jaalis imitated lace, towering edifices were not a fraction of an inch out of perfect symmetry, and the play of water and gardens alongside marble buildings recreated a semblance of paradise.

The emperor personally designed and supervised the main elements of his new city, shaped according to Hindu Vastu Shastra to resemble an outstretched bow and arrow; a format believed to be auspicious for rulers. These included the UNESCO-listed Qila e-Mubarak or the Blessed Fort, commonly now known as the Red Fort, Jama Masjid, the congregational mosque, and its towering city walls punctuated with 14 gates.

Jahanara, his beloved eldest daughter, took it upon herself to style the main thoroughfare Chandni Chowk with a canal which opened out into a pool in a square, flanked by gardens and a serai. On a clear night, the pool of water reflected the moonlight and hence the name Chandni Chowk, meaning Moonlight Square.

His nobles were then given the leeway to develop Shahjahanabad as they wished. Up came their luxurious estates, markets and workshops for every possible commodity, and dazzling temples such as Lal Mandir, Naya Mandir, and Meru Mandir to cater to the Jain business community.

Over the centuries, Shahjahanabad has been built over the most—its estates partitioned into bits and pieces, and electricity, roads and plumbing developed organically. Through all this, pockets of the Mughal era’s built heritage, markets, and cuisine have somehow survived, and even thrived.

NOTE: You may also like to read

Delhi’s Shahjahanabad Unraveled: Heritage, Sacred Places, Markets, and Food

Photo Essay: Delhi’s Red Fort, Stories Told and Untold

8. LUTYENS’ DELHI: IMPERIAL CAPITAL OF THE JEWEL IN THE CROWN

Viceroy’s Lodge [now Rashtrapati Bhawan], the epicentre of colonial rule in British India.

The new imperial capital was embellished with purpose-built shopping arcades, residential areas, and grand churches keeping British tastes and needs in mind.

Sir Edwin Lutyens’ dream to create New Delhi as a garden city lives on in its wide tree-lined boulevards.

A new chapter. New rulers. And their desire to showcase their might over the Indian subcontinent.

The 1857 First War of Independence had more ramifications than one. It brought the Mughal Empire to its end, and established in its place the British Crown as the new rulers of India with Kolkata as the imperial capital.

However, Kolkata was too far to the east, with rising rebellions against the colonial rulers.

Delhi, the historical capital placed more centrally, seemed to be a better choice. There were Hindu legends tied to it, identifying it as Indraprastha, the capital city of the Pandavas in the Hindu epic Mahabharata. Both the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Empire had used it as their seat of power. Moving to Delhi would signify divine continuity!

So, on 12 December, 1911 at the Great Delhi Durbar marking the coronation of King George V and Queen Mary, the proclamation was made: New Delhi was to be the British Raj’s new imperial capital.

A site was earmarked to the south of Shahjahanabad, and for the next twenty years construction carried out in full swing under the leadership of the Viceroy, Sir Edwin Lutyens, and Herbert Baker.

The outcome of this building marathon was a series of architectural masterpieces built to last a thousand years. That is how long the British saw themselves ruling the ‘Jewel in their Crown.’

Viceroy’s Lodge, a 340-roomed sandstone extravaganza, was erected on Raisina Hill, flanked by the North and South Blocks of the Secretariat, and the Council House. Across the manicured lawns stood War Memorial on the lines of the Arc De Triomphe.

Henry Alexander Medd’s Sacred Heart Cathedral and Cathedral Church of the Redemption provided spiritual guidance to the British officers and their families who lived in whitewashed colonnaded bungalows in large gardens on tree-lined boulevards. Connaught Place, the new commercial district, became the place to be and be seen.

New Delhi had been born.

Sixteen years later, in 1947, the colonial rulers were deposed.

And New Delhi became Modern Free India’s capital as well. ❤

NOTE: You may also like to read

A Travel Guide to Colonial Delhi

New Delhi’s Most Beautiful Church: Cathedral Church of the Redemption

– – –

Map of Delhi’s 7 historical cities and Lutyens’ New Delhi

Source: indiastudychannel.com

– – –

Travel tips and references:

I explored the above eight cities of Delhi through multiple trips over ten months using a mix of independent explorations based on binge reading and watching documentaries, audio guides, and heritage walks. Here are some of them:

- The fabulous documentary series on Rajya Sabha TV Talking History Season 1.

- The in-depth practical guidebook Delhi: 14 Historic Walks by Swapna Liddle.

- Captiva Tour Audio Guides, a goldmine of fascinating insights developed by Ravishankar Iyer and Siddhartha Kongara. [Sadly, it has since shut shop].

- Guided heritage walks. Please note none of the below have a walk schedule so you’ll have to keep an eye on their Instagram handles [links included]:

- Intach Delhi [for short, factual, sanitized walks]

- Sair E Hind [for small group, Indiana Jones-styled long discovery walks]

- Unfold Delhi [for in-depth, illustrated walks]

- Delhi By Foot [for storytelling-based walks combined with food]

- City Tales [for large (+60) seminar-type walks with a Q&A at the end]

- Karwaan Heritage [walks led by university students and professors]

- Darwesh Taleweavers [for walks combined with dramatized readings]

Such fantastic history! I loved all the buildings.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Ana. Yes, Delhi has a fantastic history, making for a great story. It is also incredible the way so many monuments have survived the ages, despite all the urbanization. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very comprehensive! This is a great summary of Delhi’s history.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Delhi is a fascinating city. I have travelled quite a bit, and must admit Delhi stands out with its rich multilayered heritage. Am happy you liked the post! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve met a number of western tourists when I’ve been in India who all said Delhi is not worth seeing, but I think it’s a fascinating place and I’ve always enjoyed exploring it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Happy to read that you chose to beg to differ. 🙂 I often feel one needs to know where to look in Delhi, as well as understand Delhi’s history. It’s true for any place, but more so for Delhi which can be overwhelming with its size, crowds, and chaos. Without the two, where to look and what these monuments mean, they are just ruins tucked away here and there. But if one knows the stories they contain, and how they all weave together, they become heritage treasures.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely agree with you. Delhi is filled with interesting remains and monuments.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent as usual

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much, as always! Delhi is incredibly multilayered. I thoroughly enjoyed digging through its many facets. 🙂

LikeLike

In terms of history and the sheer variety of rulers/dynasties, there is no other city like Delhi. There are many layers to this unique city in India.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely! When I started exploring Delhi in March last year, I thought I would be done in a week, 10 days max. It has taken me over 45 heritage walks and some 50 independent explorations to understand this city. And every now and then I still discover something more. 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

wow! 45+50 walks! that’s impressive!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hehehe. There’s lots to see in Delhi! It is a fascinating city. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I couldn’t agree more

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nice article but Delhi is also a unsafe place to travel.

LikeLike

I know it has a bad reputation. But from personal experience, I can honestly say, I have found it incredibly safe and the people super warm and helpful. I have travelled across it, to all its sights, at all times of the day and year, on my own, and not had a single bad experience. Maybe I have been lucky. 🙂 But I am grateful that the city has always treated me very kindly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I found that police are most corrupted, locals are not so helpful.

LikeLike

I am sorry you had a bad experience in the city. 😦 Travel is very personal. What is one person’s paradise can be another person’s hell. Hope you have a better time when you next here!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lovely blog on the city with the most number of heritage sites from so many different eras.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Aadil. It is always a pleasure to hear from you. And your being such a heritage buff, your comment is that much more wonderful to receive. 🙂

LikeLike

I MUST GO! Thank you for your inspiring post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Henry! I hope you do get to explore the city. 🙂 You have a very interesting blog yourself. I enjoyed reading your posts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I really appreciate that.

LikeLike

Pingback: the story of qutub minar | rama toshi arya's blog

I have been reading vineet bajpai’s Mastaan series of novels this last week . The story nestled in 1857 sepoy mutiny. Before that when I was doing my post graduation at AIIMS we used to go to qutub minar or hauz khas or lodi garden during the winters. Could not explore Delhi much although I like the exhilarating experiences of forts, mausoleum,tombs and the histories of it. I got reminded of Delhi again while reading the aforementioned book. And overnight I came across your blog. Now I feel a bit better in the sense that I can make some head and tail of the historical cities of Delhi as we have seen now. A very detailed and knowledgeable blog. Kudos and big thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Suman for your comment! It can be difficult to get one’s head around Delhi. Multiple cities, layers, and epochs make it one of the most historically rich metropolises in India, and I often feel, even in the world. As I explored the city, pretty intensely, over a couple of years, the pieces slowly started to fit, and I knew I wanted to share its overall narrative. Hence the post. Am so happy that it helped you understand Delhi better too. 🙂

LikeLike

Informative and interesting post.

Great effort to reveal the many layers of Delhi .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your kind words. Delhi is a fascinating city. A melting pot of multiple historical epochs and peoples, unlike any other. Am grateful that you feel I have been able to do some justice to this, unfortunately often downplayed, world city. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: a guide to solo travel in afghanistan for the indian traveller | rama toshi arya's blog