The Golden Man.

Ubiquitous with Kazakhstan, look closely and you will find him everywhere. Atop Almaty’s Independence Monument, in promotional cut-outs during events such as the recently held World Nomad Games, in state museums across the country, and both commemorative and currency coins.

He is the most celebrated son of Kazakh soil.

An 18-year-old Saka warrior prince [or princess] who lived in the 4th Century BC, his burial mound was found in April 1970. Purely by chance, as is usually the case. Inside the heap of rubble was a skeleton sheathed in over 4,000 pieces of pure gold from top to toe, holding weapons ready to go to war. The burial was the first in Central Asia, and with the largest gold hoard, to be discovered intact and not plundered. Ever.

Though the most famous, he is, however, not Kazakhstan’s only ‘Golden Man.’ Nine more have been unearthed after him, including four women, who like him were also draped in gold ornaments. Each with a unique story that is theirs alone.

Welcome to my photo essay on the Golden Man, where I share stories with you about him. Some told. Some untold. So, next time that you see him, he is no more a stranger, but almost a friend. 😊

Almaty’s grandest square holds in its centre a towering 91-feet-tall column topped with the Golden Man on a mythical winged leopard. An apt combination. The square is Republic Square, the ensemble inside it the Independence Monument, and the Golden Man which became Kazakhstan’s national and cultural symbol on the country’s independence in December 1991.

Golden Man’s burial mound [kurgan] is one of 80 in the Esik necropolis located on the Great Silk Road, 50 kilometres east of Almaty city. All, except his lone one, had been plundered of their goods in antiquity. Six metres high, and sixty metres wide, his was found, by some miracle fully intact, during excavations for the new automotive base planned to be built at the site.

Part of the State Historical-Cultural Museum-Reserve Issyk, the above kurgan’s cross-sectional excavation throws light on the layout of the tomb and burial niche. [No, it is not the Golden Man’s burial mound.]

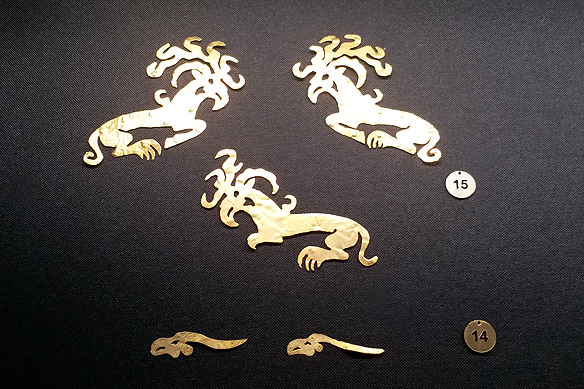

It is befitting that a museum was opened at the Saka-era Esik burial mounds to celebrate a finding of such magnitude. Surrounding a recreated Golden Man in the museum’s main hall are items unearthed from the mounds. These range from pottery to the gold plaques which adorned his dress and hat.

The Sakas were an ancient Central Asian nomadic people of Iranian ethnicity adept at horsemanship, battle, and metalwork. They lived in the Kazakhstan steppes from the 8th to 3rd Century BC.

Christened simply as the Golden Man, there is an equal chance that the warrior, in fact, was a woman. Female warriors dressed in armour, boots, and hats, brandishing their swords, were common amongst the Sakas.

Unfortunately, it is too late to determine the corpse’s gender. When the archaeologists came across the burial niche and its astounding collection of gold, they got so excited with their find, they focussed on the artefacts and put the bones in a cardboard box instead, with the note: “The Golden Man, May He Rest in Peace.” Fifty years later, by the time the box found its way back to archaeologists, the bones were beyond salvage. Or a DNA test.

There is a reason why he is called the Golden Man, and why scientists refer to him as ‘Kazakhstan’s Tutankhamen.’ Lying inside a sarcophagus made of huge fir logs inside one of the Esik burial mounds, his skeleton was sheathed with gold.

An armour comprising 4,000 gold plaques embroidered on to leather, high boots also embossed with gold, and a pointed head-dress embellished with 150 gold pieces fashioned into winged horses, a snow leopard, mountain goats, birds, and motifs. In addition, he was surrounded with jewels, and gold and silver vessels.

Every single gold artefact you see in Kazakhstan’s various Golden Man museum collections, housed behind glittering sheets of polished glass, is a meticulously detailed copy. Replete with dents or scratches. Of course, they are in pure gold. Just like the originals. But they are not 2,400-years-old. The originals lie locked away in impregnable government vaults, safe from any possible modern-day plunder or decay.

Equestrian nomads on earth, the Scythians or Sakas [the former more common name courtesy the Ancient Greeks], hoped to continue their affinity with horses in the afterlife as well. Experts at archery whilst riding, any surprises then that their burials included these animals in all their battle finery [also in gold], and some extra harnesses as well!

Whilst it no doubt adds to the enigma surrounding the Golden Man—that he is perhaps the sole survivor from the annals of time—the truth is Kazakhstan’s burial mounds have revealed nine more golden men and women.

These include: The Sarmatian Chieftain of Araltobe, King of Berel, Princess of Miyaly, Chieftain of Taskopa, Urjar Priestess, and the golden men of Taldy-2 and Eleke-Sazy, amongst others. There’s also the Golden Man of Shiliktinskaya Valley who was dug up in 2003 and then dug back into his tomb ten years later because local residents’ were convinced climate change and its related calamities were his curse in action.

Who knows how many more golden men and women, and what all they decided to pack along, are still waiting in the wings.

The best place to come face to face with these folks from antiquity is at the Hall of Gold in Astana’s National Museum of the Republic of Kazakhstan where their faces have been reconstructed using state-of-the-art research and technology.

One of the Golden Men discovered in 1999 was the Sarmatian Chieftain of Araltobe. Sarmatians were a group of nomadic tribes who occupied the region after the Sakas. This gentleman dates to the 3rd Century BC and was buried in north-west Kazakhstan along with his swords and 400 gold objects.

Burial niches of the Golden Women came replete with gold jewellery, makeup kits, and mirrors. One of them, belonging to a Saka princess buried in western Kazakhstan, is 2,500-years-old—the oldest burial so far discovered in the country. Wrapped in a blanket decorated with gold plaques, the Zoroastrian lady’s paraphernalia included gold and silver vessels, horse bridles, household items, and a little wooden comb with a battle scene between the Sakas and Persians.

Kazakhstan’s first Golden Man has travelled far and wide as part of the ‘Golden Man Procession through the World’s Museums’ since 2017. He has been to Azerbaijan, Austria, Belarus, China, France, Germany, Greece, India, Italy, Macedonia, Malaysia, Poland, Russia, South Korea, Turkey, and United States to name a few. But no matter where he goes, you will still bump into him no matter where you go to in Kazakhstan. ❤

– – –

[This blog post is part of a series from my 14-day solo independent travels across Kazakhstan in August–September, 2024. To read more posts in my Kazakhstan series, click here.]

How fascinating! I must admit before I read this post, I wasn’t aware of the Golden Man of Kazakhstan. No wonder some liken him to Tutankhamen. You just gave me a very strong reason not to skip Astana when I travel to this country one day.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Oh, you must not miss Astana at all. It is a fabulous city. Writing about it right now. Do take one of the English speaking guides at the Astana Museum. Trained historians, they bring Golden Man’s story beautifully alive.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: astana aka nur-sultan, the brand new capital for an ancient heritage | rama toshi arya's blog

Pingback: 36 hours in almaty | rama toshi arya's blog

Pingback: travel guide: the six untold treasures of kazakhstan’s silk road heritage | rama toshi arya's blog