Welcome to my travel guide on royal Hue.

Often reduced to an overnight visit enroute to colourful Hoi An or sidelined completely for Vietnam’s buzzing metropolises and beach cities, Hue is where Vietnamese history and culture bask in full authentic glory.

For 143 years, from 1802 to 1945, the city on the banks of the Perfume river in the middle of the country served as the capital of the Nguyen dynasty, Vietnam’s last royal ruling family. Prior to this, Hue had been the capital of their predecessors—the Nguyen Lords, a feudal noble clan, since 1558.

The Nguyen empire marked a period of dramatic flux in the country’s history. Starting off as an isolationist Confucianism-driven kingdom of unified Viet Nam, it morphed into a military might to reckon with, on to an eclectic marriage of European and Vietnamese cultural elements, before being ousted in 1945.

Thirteen Nguyen emperors ruled from Hue’s Imperial Citadel during these years—a fortress-cum-administration centre-cum-royal residence. It is where military decisions to conquer neighbouring lands, followed by agreements to relinquish the same lands to French colonial rulers were drawn and sealed.

In and around the city, seven of Hue’s 13 emperors designed and built their grand tombs to be remembered by. These reflected not just their personalities, philosophies, and aspirations as rulers, but also the prevailing geopolitical scenarios.

Whilst the UNESCO-listed Imperial Citadel and royal tombs took care of the Nguyen emperors’ lives and afterlives, patronage of spiritual places continued unabated. An age-old royal practice, it ensured the gods were kept happy and added a touch of divinity to dynastic rule.

Yes, Hue has all this and even more!

Dear Reader, I hope you find this travel guide useful as I take you along Hue’s imperial history, connecting its rich and varied monuments to the city’s incredible story. ❤

Table of Contents:

- Hue’s Imperial Citadel and very own Forbidden City

- Gia Long Tomb: The under-rated mist-clad tomb of an empire’s founder

- Minh Mang Tomb: The ‘Vietnamese’ tomb for a warrior-king

- Thieu Tri Tomb: The countryside tomb for a frugal emperor

- Tu Duc Tomb: A tomb for a depressed poet-emperor to write poetry

- Duc Duc Tomb: A tomb for the emperor who ruled for three days

- Dong Khanh Tomb: A tomb for a pro-French figurehead emperor

- Khai Dinh Tomb: The flashiest imperial tomb funded by a 30 percent tax

- An Dinh Palace, home of Vietnam’s last emperor

- An Hien Garden House, a peek into elite Nguyen life

- Hue as Nguyen Empire’s spiritual centre

- Thien Mu Pagoda, Hue’s oldest and most famous pagoda

- Tu Hieu Pagoda, Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh’s home

- Bao Quoc Pagoda, the ‘national temple’

- Completing Hue’s royal circuit

- Nam Giao Esplanade, esplanade of sacrifice to the heaven and earth

- Tiger Arena, battle scene of royal elephants and claw-less tigers

- Thanh Toan Bridge, a sacred bridge and the ordained Mrs. Tran

HUE’S IMPERIAL CITADEL AND VERY OWN FORBIDDEN CITY

For 142 years, the Imperial Citadel in Hue was Vietnam’s political, military, and cultural centre. After uniting north and south Vietnam, Gia Long, the founder of the empire, set about building the Citadel and within it a Forbidden City on the same lines as that in Beijing in 1803. Subsequent rulers made additions reflecting their individual tastes.

It is a huge complex with gardens, meandering paths, restful pavilions, and grand palaces laid side by side. In 1945, when the empire split back into north and south Vietnam once again, there were 148 edifices inside the 6-metre-high city walls surrounded by a moat. Post the war, this has shrunk to around 20.

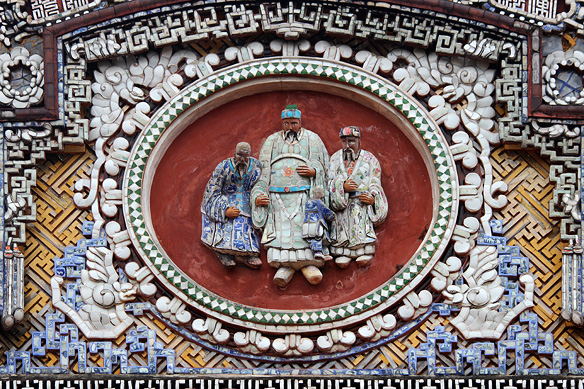

Must see sites include The Mieu, the Confucian royal ancestral shrine for Vietnam’s emperors with Nine Dynastic Bronze Urns in the courtyard, each in memory of an emperor. The largest, weighing 2,600 kilograms is dedicated to Gia Long. Thai Hoa Throne Hall is where coronations, birthday celebrations, and court rituals took place. The imposing Meridian Gate topped with Five Phoenix Pavillion contains a fabulous collection of royal gold seals. Finally, the restored ceramic mosaic-encrusted Kien Trung Palace built by Emperor Khai Dinh is where he, and later his son Bao Dai lived.

Note: UNESCO-listed royal court music performances are held daily at the citadel’s royal theatre. Check timings.

GIA LONG TOMB:

THE UNDER-RATED MIST-CLAD TOMB OF AN EMPIRE’S FOUNDER

Two words best describe Nguyen empire’s first tomb: Atmospheric. Untouristy. Twenty kilometres south of Hue, the understated and deserted mausoleum built in 1820 on the mist-draped lush banks of the Perfume river belie the importance of its owner.

Emperor Gia Long [r. 1802 – 1820], founder of the empire, not only unified north and south Vietnam, moving the capital from Hanoi in the north to centrally located Hue. He also coined the country’s name and gave the 19th Century state a Confucian identity. The name Viet Nam, meaning ‘people of Viet,’ is his legacy.

His tomb comprises graves of him and his wife, a worship area [to the right], stele [to the left] and two tall towers across a lake. Part of an expansive burial complex housing royal family members, Gia Long’s resting place is a bit of a walk from the ticket booth at the gate. Golf carts are available.

MINH MANG TOMB:

THE ‘VIETNAMESE’ TOMB FOR A WARRIOR-KING

Emperor Minh Mang [r. 1820 – 1841] carried his father’s legacy forward, dedicating his 21-year reign to expanding the empire, crushing rebellions, and shielding Vietnam from the French. At its height, the empire encompassed all of present-day Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam.

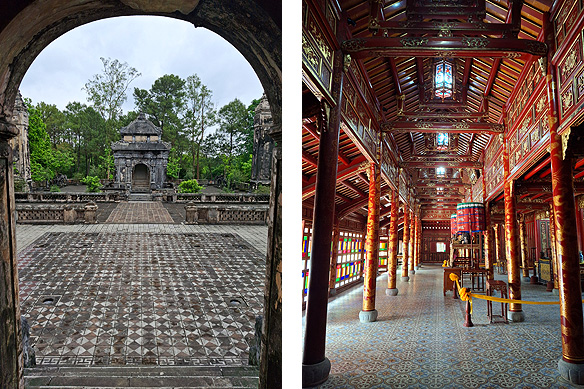

His large orderly tomb dated 1843 and completed by his son, reflects both his times and his role as a warrior-king. Sans any trace of foreign influence, the architectural features which typify a Nguyen imperial tomb are lined up in a single neat row.

First in line is the honour courtyard and its 20 huge statues that represent his entourage in the afterlife. Next comes the stele house listing his achievements followed by the tomb area with its lacquered buildings for prayer and rest decorated with dragons and phoenixes. Behind them all is the tomb itself, encased in a circular wall with a doorway that still opens only once in a year. On Minh Mang’s birth anniversary.

THIEU TRI TOMB:

THE COUNTRYSIDE TOMB FOR A FRUGAL EMPEROR

Sandwiched between two powerful personalities, his father Minh Mang and son Tu Duc’s reigns, Emperor Thieu Tri is best remembered for trying to keep the French out. Unfortunately, neither his mandarins nor the French, who used missionaries as a guise, took his orders seriously. Things eventually came to a head with the French destroying Nguyen forts and ships.

Frugal, conservative and a strict adherent of Confucianism like his father, Thieu Tri [r. 1841 – 1847] also never got around to building a tomb for himself. That is, till he was on his deathbed at 40 with 64 children.

His tomb was built by Tu Duc, his second eldest son, in 10 months and without any protecting wall or decorative excesses, keeping Thieu Tri’s values in mind. It lies surrounded by emerald green rice paddies; the restrained layout borrowed from that of Gia Long and Minh Mang’s tombs.

TU DUC TOMB:

A TOMB FOR A DEPRESSED POET-EMPEROR TO WRITE POETRY

Vietnam, which had so far succeeded in warding off French colonial pressure, started to slip through the imperial fingers under Emperor Tu Duc’s [1847 – 1883] reign. To add to his woes, he was unable to sire a child. Depressed, he turned towards poetry and building his enormous tomb-cum-recreational park in the midst of a pine forest in 1864.

Thousands of workers toiled day and night for four years on it, until everyone got fed up and rebelled. To appease his subjects, he renamed his haven from Van Nien Co [Palace of Eternity] to Khiem Cung [Palace of Modesty]. Here he whiled his hours reading, writing, watching plays, and drinking tea, surrounded by landscaped gardens, poetic lakes, and ethereal pavilions. All with the word ‘Khiem’ in their names.

A colossal 20-ton stele in front of the main tomb area records the countless achievements made during his 36-year reign in his own handwriting. Some claim that he is not really buried here though. That his servants buried him in a secret place inside the grounds and were then executed to keep the secret intact.

DUC DUC TOMB:

A TOMB FOR THE EMPEROR WHO RULED FOR THREE DAYS

What happens when one has only been on the throne for three days and then dies. He still gets a grand-ish tomb in keeping with Nguyen imperial protocol.

Since Emperor Tu Duc could not have offspring, the throne went to his nephew Duc Duc, who ruled from 20 to 23 July, 1883, after which he was deposed aged 31 and a father of 19 children. As the empire’s 5th emperor, he is buried in Hue City, along with his wife, son, and grandson. The mausoleum, built in 1889 by his emperor son, is the least ambitious of Hue’s seven imperial tombs, but warrants a visit, perhaps, for this very reason.

Comprising of a shrine and burial area, the surrounding fields are home to broods of chicken and mooing cows. You will also most likely be the only visitor to have walked through the entrance that day.

DONG KHANH TOMB:

A TOMB FOR A PRO-FRENCH FIGUREHEAD EMPEROR

A short walk from Emperor Tu Duc’s poetic magnum opus is the sombre tomb of Nguyen dynasty’s 9th Emperor Dong Khanh. Belonging to an era when Vietnam was officially a French colony and the emperors ruled in name only, the tomb, renovated by Emperor Khai Dinh, marries eastern traditional wooden shrines with western concrete and iron structures.

After ruling for four years, Dong Khanh had died young, aged just 24 in 1889. He was not the French colonial rulers’ first choice. His half-brother, who they chose, had run away and taken refuge in the highlands to wage a rebellion. The French responded by placing Dong Khanh, who liked all things luxurious and European, on the throne instead.

The real highlight, however, of a visit to Dong Khanh’s tomb is the many royal family tombs scattered around the grounds. Encrusted with exquisite ceramic mosaics, they lie hidden behind towering pine trees which echo with the deafening hum of thousands of crickets.

KHAI DINH TOMB:

THE FLASHIEST IMPERIAL TOMB FUNDED BY A 30 PERCENT TAX

One of Hue’s mandatory attractions, Emperor Khai Dinh’s [r. 1916 – 1925] tomb tends to evoke a mixed bag of emotions. From gasps of awe at its sumptuous ceramic mosaic interiors and black concrete dragons to snorts of disdain for the very same. After all beauty is subjective.

Ten years in the making, the tomb completed in 1930 is an eclectic mix of East and West, reflecting colonial France’s complete hold on the empire by this time. It is also Nguyen dynasty’s last architectural work. Though the smallest of Hue’s seven imperial tombs in terms of area, it is the flashiest and most labour-intensive. The five levels sliced onto a hill, culminate in the ornate Thien Dinh Palace reached by 127 steps. His coffin lies 18 metres under it in a crypt.

Khai Dinh, who was hated for his ties with the French and for imposing a 30 percent tax on the Vietnamese to fund his vanity, did not live to see the completed tomb. It was completed by his son Bao Dai, Vietnam’s last emperor.

AN DINH PALACE, HOME OF VIETNAM’S LAST EMPEROR

Two wives, one a beautiful Catholic Vietnamese and the other a French citizen, with six mistresses in-between summarizes Vietnam’s last Emperor Bao Dai’s love life. And also, perhaps reflects his seesawing professional allegiances.

From loyalty to the French when he ascended the throne in 1932 to the Japanese at the end of WWII in 1945. From Ho Chi Minh’s communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam to anti-communist groups, and back full circle to the French as their Chief of State of Vietnam in 1949, till he was ousted from office in 1955. Ultimately Bao Dai moved to Paris as an exile, where he died in 1997.

The emperor loved the good life, and the closest one can get to him in present-day Hue is at his family home, An Dinh Palace. Built by his father, three of the 10 original structures still stand, including an ornamental gate. Look out for the large paintings of the royal tombs by an unknown artist in the foyer of the 22-roomed neo-classical main building. In the centre is a bronze statue of young Bao Dai holding an empty court.

AN HIEN GARDEN HOUSE, A PEEK INTO ELITE NGUYEN LIFE

During Nguyen times, the royal relatives and mandarins [government officials] lived in lovely garden houses made of wood and brick on the banks of the Perfume river. These pillared houses in Vietnamese style based on Feng Shui principles, were surrounded with manicured gardens and water features, hence the name Garden House.

Though many of them have been converted into luxury hotels, a few have opened their doors to day-trippers. An Hien Garden House, a few metres away from Thien Mu Pagoda, is one such.

Built in the late-19th Century, the 48-pillared, 3-sectioned structure started off as the residence of the 5th Emperor Duc Duc’s 18th daughter. Since then, it has changed hands a few times. UNESCO-listed Vietnamese court music performances are held every day in the outhouse at 9 am and 3 pm.

HUE AS NGUYEN EMPIRE’S SPIRITUAL CENTRE

Historically, three pagodas have formed the spiritual centre of, both the Nguyen dynasty and their predecessors, the Nguyen Lords. As a bonus, each of the three comes with its own inimitable story.

But first, a little explanation on terminology. Vietnam’s religious sites comprise of ‘pagodas’ and ‘temples.’ They mean two very different things. Pagoda refers to a Buddhist complex in its entirety—the tower, place of worship, monks’ dwellings, and tombs of its abbots. A ‘temple’ on the other hand is dedicated to Confucianism, Taoism, or wise military figures in history.

Thien Mu Pagoda is Hue’s oldest and most famous pagoda. Built in 1601 by the first Nguyen Lord, its name means Heaven Fairy Lady Pagoda and is a reference to the Vietnamese origin myth. Towering over the complex is present-day Hue’s religious icon, Phuoc Duyen Tower, an octagonal seven-storey-high edifice put up by Nguyen Emperor Thieu Tri in 1844.

Oozing with Zen peace in contrast, is the under-the-radar Tu Hieu Pagoda tucked behind a verdant grove. Built in the trademark style of the poet-Emperor Tu Duc, it housed Vietnam’s most famous monk—the global spiritual leader, poet, peace activist and Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh—till his death in 2022. Also within the complex is a collection of 24 tombs belonging to Nguyen court eunuchs. Bereft of family or children, they bought the piece of land to give themselves a safe resting place.

And then there is Bao Quoc Pagoda, perched atop a flight of steps behind a market, dating to 1670 and filled with cheerful novice nuns and monks. A ‘national temple’ during Nguyen emperors’ rule, it transitioned into a ‘pagoda’ in 1935 when a monastery was added. The complex has been renovated multiple times, the most recent being 1957. To attend a chanting session, you will need to enter the main hall from the rear entrance.

COMPLETING HUE’S ROYAL CIRCUIT

Three Nguyen empire sites, one in the city, and two surrounded by rice paddies in the hinterland, complete Hue’s royal circuit.

Nam Giao Esplanade [in Hue] is where the Nguyen emperors made sacrifices to the ‘heaven and earth’ in an elaborate spectacle every year from 1803, right till the empire’s demise in 1945. Part of the UNESCO-listed Complex of Hue Monuments, the ritual worship was revived in 2004 as a biennial event in the Hue Festival, replete with the same pomp and ceremony.

Out in the countryside is the open-air Tiger Arena built by the second Nguyen Emperor Minh Mang. Forty-four metres wide, the arena was used for training elephants in war combat by pitting them against tigers in a fight-to-death battle. To ensure the elephant, who symbolized royal power, always won, both the fangs and claws of the tigers were first cut off. The arena was last used in 1904.

Last, but not least, is the poetic Thanh Toan Bridge draped over an irrigation canal in Thanh Thuy Chanh Village. Handiwork of a high-ranking mandarin’s childless wife Mrs. Tran Thi Dao to gain merit, it dates to 1776. The Nguyen connect? In 1925, Emperor Khai Dinh sanctified the bridge and ordained Mrs. Tran a saint with an altar dedicated to her inside, so she would bless the villagers and, maybe, also whosoever made the journey this far. 🙂

– – –

Travel tips:

- Staying there: I stayed at the La Vela Hue Hotel. Though outside the city-centre, its rooms, breakfast spread, and service were brilliant. The fact that it’s next to the Aeon Mall came in handy.

- How many days: I stayed for seven days, six nights.

- Getting around: I explored the Imperial Citadel on a walking tour and the Tiger Arena and Thanh Toan Bridge [out in the countryside] on a motorbike tour. For the seven royal tombs and other sites I took a Grab taxi [reasonably priced]. You can download the app from its website here.

[Note: This blog post is part of a series from my travels to Vietnam for three weeks in March 2025. To read more posts in my Vietnam series, click here.]

It looks a wonderful place.

LikeLike

It is lovely. 🙂 Thank you for stopping by.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Rama for the beautiful and haunting pictures and information about the Imperial Citadel and Tombs of Hue which look pretty much like they did in 1994 when I visited the Palace and tombs of Kai Dinh and Tu Duc – almost deserted apart from the occasional Vietnamese woman dressed in Ao Dai. This must be one of the quietest part in Vietnam apart from in the mountains! I found it to be an aesthetically pleasing if rather sad experience. Sad because of the amount of money, labour and time expended in creating such extravagant buildings when most people lived in abject poverty and not surprisingly as you mentioned the workers rebelled. Then I guess you could say that about so many buildings from the pyramids on. I think its the emptiness of the place that made me sad. But then thankfully at least its not been turned into a disneyfied historical experience like so many other sites which will remain nameless. Contradictions abound …

I also enjoyed seeing your picture of the Tien Mu Pagoda where I had another experience which has stayed with me. As I entered the complex I was approached by a one legged man with a crutch and I gave him some money. After some time he came up to me again tugging at my sleeve and I motioned that I had already given him something. He simply pointed me in the direction of the tour guide and group leaving at the other end of the site while I was wandering off in a different direction. ‘Instant karma’ – a good action rewarded? Certainly a lesson that I have never forgotten.

LikeLiked by 2 people

So beautifully written. As I have said before, I really think you should write a blog! Yes, karma is often instant. We don’t need to wait for another lifetime for it. 🙂

LikeLike

Hue is a great city, and it does deserve more time than quick stop. We went to several tombs after visiting the Imperial City. I recognize Kai Dinh from your pictures, but can’t remember which others we saw without looing at my notes. Maggie

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hue’s a treasure. I especially enjoyed the tombs off the tourist circuit — Gia Long, Duc Duc, and Dong Khanh’s, along with Thich Nhat Hanh’s monastery!

LikeLike

How impressive that you managed to visit so many royal tombs around Hue! I only went to three: that of Minh Mang, Tu Duc, and Khai Dinh. The first one was my favorite, though, for its expansive and lush setting.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I planned my travels in such a way that I could explore all seven. 🙂 Spent a week in the city. I had read about the tombs before and found the sheer variety and how they fit into Vietnam’s story fascinating. I would not mind revisiting the city either! It is easily one of my favourites.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: vietnam’s capital hanoi, stories told and untold | rama toshi arya's blog

Pingback: 72 hours in ho chi minh city | rama toshi arya's blog

Wonderful place 💓

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hue is indeed beautiful. Full of heritage and old-world charm. 🙂

LikeLike