Before Rome. Before even Constantinople. The first one to officially adopt Christianity was Armenia. Saint Gregory the Illuminator had miraculously healed King Tiridates III who had lost his mind. In gratitude, the King declared Armenia a ‘Christian’ country. It was the year 301.

A century later, in 405, the brand-new State religion introduced a brand-new script to spread ‘God’s word.’ Mesrop Mashtots, a cleric-cum-linguist, was assigned the task of creating an alphabet that would encompass the phonetic expanse of the Armenian language, a standalone member of the Indo-European language family. Over time, the scope of this script increased to document Armenian philosophy, science, and the arts.

Monasteries, as centres of faith and learning, soon cropped up across the Kingdom in breathtaking settings. Perched over canyons, atop sheer cliffs, and in verdant valleys. In the medieval era, there were tens of thousands of these. As Armenia’s realm shrunk, these reduced to a mere few thousand with four of them now UNESCO-listed.

Known as the Armenian Apostolic Church, Armenian Christianity is based on the teachings of the two early Apostles, Thaddeus and Bartholomew. What is more remarkable is that the Armenians resolutely stuck to the original version of their faith for the next 1,700 years, amidst the whirlpool of conversions, genocide, and wars that swept through the region.

Welcome to my photo essay on the most spectacular monasteries of the lot that have survived to date—each with something that sets it apart. Sometimes it is its story, sometimes its location, and sometimes its incredible art. I have punctuated these photos with those of my favourite Armenian manuscripts in Yerevan’s Matenadaran.

Wishing you happy travels, always. ❤️

Khor Virap: This is where it all started. Saint Gregory the Illuminator, arch enemy of the State, was imprisoned right here in a deep dungeon for 13 long years by King Tiridates III. His crime: his father had killed the King’s father. When Tiridates went looking for him to heal him of his madness, he found a malnutritioned, but alive Gregory. A kind woman had been throwing him a loaf of bread every day. Close by, on a hillock, is a vantage point looking out at Azerbaijan, Iran, and Turkey, along with Armenia’s best views of Mount Ararat, site of the proverbial Noah’s Ark.

![History of Armenia by Movses Khorenatsi [5th Century], 16th Century.](https://ramaarya.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/armenia-manuscripts-9.jpg)

History of Armenia by Movses Khorenatsi [5th Century], 16th Century.

After converting Armenia into a Christian country, Saint Gregory the Illuminator established Armenia’s first monastery Geghard, the ‘Monastery of the Spear,’ setting into motion a tradition that was to become an intrinsic part of the Armenian identity. If you wondering about the name, for 500 years the monastery housed the Longinus Spear that pierced Jesus; it was brought to Armenia by the Apostle Thaddeus. The spear is now on display in the Echmiadzin Treasury Museum.

Patrons continued to add buildings to the site till the 13th Century, which remains in use even today. You will most likely share the UNESCO-listed monastery, carved into living rock in the picturesque Azat Valley dotted with caves used as monks’ cells, with an Armenian wedding or baptism ceremony in all its timelessness.

Royal Gospel by scribe and painter Sarkis Pitzak, 1336.

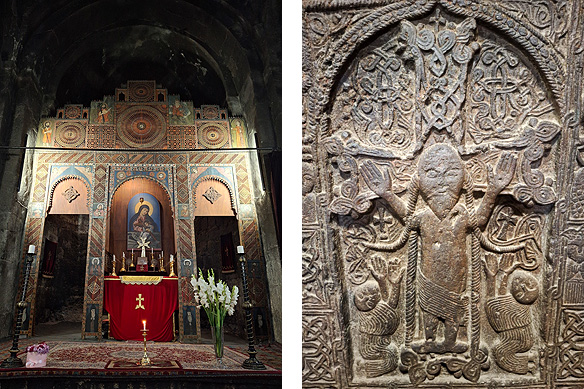

Armenian monasteries are typically austere, sans any decoration; the khachkars and wall engravings, if present, only to announce memorials and donations. In stark contrast is Akhtala’s vibrant Byzantine frescoes dated 1205 – 1216, filled with haloed saints. These splendid works of art are next-door Georgia’s influence. The collection includes a fresco of the Virgin Mary behind the altar with a vandalised face. By a quirky twist of fate, the hole turned out to be bang in the middle of the sculpted cross on the outer wall. Divine intervention. 🙂

Self-portrait of Painter Tzerun, 14th Century.

There is no shortage of fantastical legends in Armenia, and the 7th – 13th Century Harichavank monastery with its famed scriptorium has more than its fair share. Mainly built around the Seljuk attacks, these range from Armenian devotees who turned into doves to escape capture to the monastery’s invincible structure that refused to be destroyed. The most charming though is the story of the young lady who was running away from the invaders and the cliff sliced into two to protect her. A small chapel marks the spot where she took refuge.

Deep in Armenia’s south is the country’s most famous monastery—Tatev. Dated 9th Century, it stands on the edge of a monumental verdant gorge traversed by the Guinness-listed cable-car ‘Wings of Tatev.’ In addition to its magnificent setting, Tatev’s second claim to fame is its medieval university, a centre for learning and miniature painting which safeguarded Armenian culture through Ottoman and Persian rule in the 14th and 15th centuries.

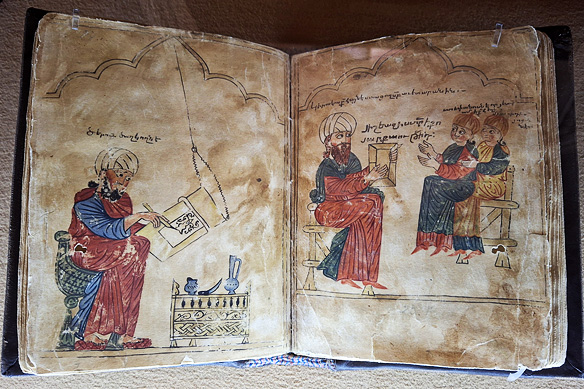

![Grigor Tatevatsi [1346 - 1409] with his Disciples, 1449.](https://ramaarya.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/armenia-manuscripts-2.jpg)

Grigor Tatevatsi [1346 – 1409] with his Disciples, 1449.

Noravank is my favourite monastery in Armenia. I am not too sure whether it is because of the way its 13th – 14th Century apricot stone churches seem to rise out of the very apricot rocks they stand on, high up in the arid mountains. Or whether it is because of the quirky design features. A pair of stairs leading to a door up in the air. The elaborate relief over the doorway with a bearded God the Father. Or maybe it is because of its soulful story.

According to an Armenian legend, the Prince of Syunik commissioned architect-sculptor-miniaturist Master Momik, who was in love with his daughter, for this task, but had him thrown off the building just before its completion. He was not too happy about having a commoner as a son-in-law. Momik is buried where he fell to his death.

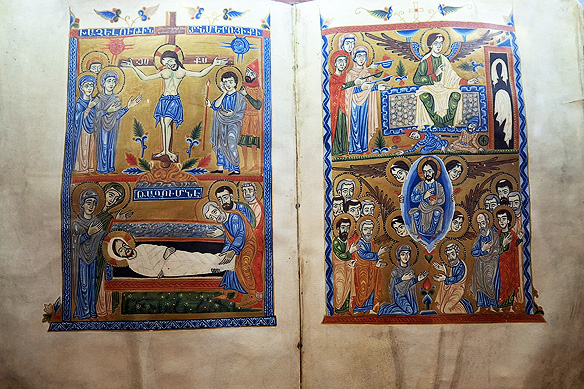

![Gospel by scribe and painter Avag in Sultania [Tabriz], 1337.](https://ramaarya.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/armenia-manuscripts-5.jpg)

Gospel by scribe and painter Avag in Sultania [Tabriz], 1337.

Another monastery that wins hands down when it comes to location is Sevanavank, surrounded with the silk-smooth waters of Lake Sevan. Comprising of two churches, one dedicated to the Apostles and another to the Mother of God, the monastery was established by Bagratid Princess Mariam in 874. Luckily for the traveller, there is something more to marvel at—a 12th/ 13th Century khachkar with a crucified Mongol-faced Jesus with plaits. The rationale? The belief that the invading Mongols would not destroy buildings where the gods looked like them.

Book on Human Nature, 13th – 14th Century.

UNESCO-listed 10th Century Sanahin monastery in Lori province is steeped in an enigmatic aura. Tall trees compete with a taller belfry in an ensemble which includes an 11th Century Academy and Bookstore, and graves of the royal family. A renowned school for illustrators and calligraphers, many a jewelled manuscript was written here and many a monk became a scholar, surrounded by around fifty of Armenia’s most exquisite khachkars.

Sharing UNESCO space and fame with Sanahin, is Haghpat, three kilometres away. Considered to be one of the highpoints of Armenian religious architecture, the 10th Century monastery was commissioned by Bagratid Queen Khosrovanuysh in 976, and thereafter added to by subsequent rulers till the 13th Century. It is the proud home of a stunning fresco and an unusual khachkar. The latter, dated 1273, and only one of ten such, depicts a crucified Christ instead of the cross in its Armenian ‘tree of life’ avatar.

On Medicinal Herbs, 18th Century.

Sitting guard outside Goshavank monastery is Mkhitar Gosh, the 13th Century multi-talented author who had rebuilt it. Hence the name Goshavank, Gosh’s monastery; Vank is an Armenian suffix meaning monastery. Gosh also wrote Armenia’s first criminal code and set up one of the country’s finest medieval schools inside the unwalled complex which lies amidst green meadows, surrounded with villages. Its simplicity belies its treasures, or should I say one particular treasure: a 1291 khachkar aptly named the ‘needle-carved’ for its intricate layered filigree work.

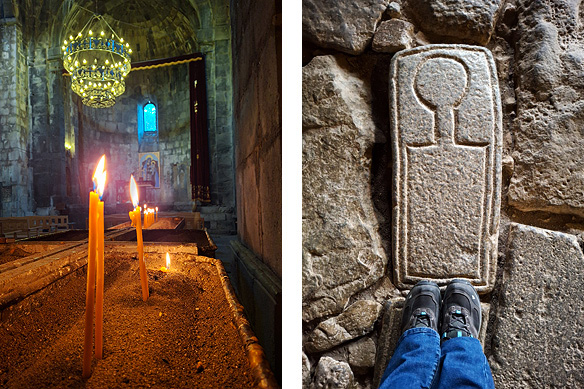

A curtain rod and a [usually] maroon curtain hanging on one side of the altar signifies that an Armenian church is functioning. Even if it hangs in a crumbling medieval monastery. Saghmosavank monastery is especially popular with weddings. It is hard to beat an 800-year-old cluster of churches perched over the steep Kasakh gorge as a venue. More so, if it is also the site of an extinct 4th Century church built by Saint Gregory the Illuminator himself wherein he taught the Psalms to the priests. Saghmosavank translates as Monastery of Psalms.

![The bringing forth of the creatures of the waters and the fowls of the air, The creation of the beasts of the earth and of man [Upon the 5th and 6th days of the Act of Creation], Gospel, 15th Century.](https://ramaarya.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/yerevan-matenadaran-2.jpg)

The bringing forth of the creatures of the waters and the fowls of the air, The creation of the beasts of the earth and of man [Upon the 5th and 6th days of the Act of Creation], Gospel, 15th Century.

Fret not if it isn’t perfect weather whilst exploring Armenia’s monasteries. Some look pure magic wrapped in mist such as the Haghartsin monastery near Dilijan, Armenia’s favourite hill-station. Nestled between the lush mounts, the 10th Century monastery boasts a massive refectory and atmospheric churches. Its most recent renovation in 2011 was funded by a Muslim, the ruler of Sharjah, Sultan bin Muhammad Al-Qasimi.

In Armenia’s sea of monasteries, one stands head and shoulders above the rest. It is Echmiadzin, the Mother Church of Armenia. Fresh out of an extensive restoration of its interiors decorated with magnificent Persian-styled frescoes, Echmiadzin is Armenia’s first church, and the oldest cathedral in the world. Saint Gregory the Illuminator had founded it in 301 after the country made Christianity its official religion. Since then, it has been rebuilt and added to continuously, right up to recent times, and includes a monastery and treasury museum. The latter possesses an enviable collection of Christian relics with the Longinus Spear that pierced Jesus, and fragments of the cross he was crucified on and of Noah’s Ark, as its star attractions.

Not too far away are a pair of historical churches housing remains of two of the 37 Christian Virgins [Hripsime and Gayane] who had escaped persecution in Rome, only to be executed in Armenia, and the ruins of Zvartnots, a 7th Century three-storeyed cathedral. Together, these comprise Armenia’s most sacred and famous UNESCO-listed heritage site. A perfect ode to King Tiridates III, Saint Gregory the Illuminator, and Mesrop Mashtots, who changed the course of Armenia for keeps.

![Hymn by Mesrop Mashtots [361 – 440], 1308.](https://ramaarya.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/armenia-manuscripts-4.jpg)

Hymn by Mesrop Mashtots [361 – 440], 1308.

I hope you enjoyed this last and final post in my six-part Armenia series. If you would like to read any of my other Armenian posts, they are all here. Thank you for coming along with me on this journey.

[Note: I travelled solo and independently across Armenia for 12 days in September-October, 2025.]

Those centuries-old monasteries and churches are among the main reason why Armenia has been on my wish list for quite some time now. The khachkars, the carvings, the architecture, and the setting are just stunning, not to mention the long history of each place. Thanks for the virtual tour, Rama.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Armenia was long on my list too. As far back as I can remember. 🙂 Am glad I got to see it in some depth, and that you enjoyed what I wrote.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A great post Rama of the most awesome monasteries which as you say seem to grow out of their surroundings and look like they are there for eternity having survived centuries of destruction and oppression. Similar architectural features but all so different because of the variety of their surroundings. I guess the most memorable for me is Khor Virap looking reflectively over the border at Mount Ararat now on Turkish soil. I also liked your favourite Noravank and climbing those stairs and wondering why am I doing this?! And Sevanavank perched above the airy misty lake. All so remarkable and memorable in their different ways. And what riches in those manuscripts some of which remind me of the early Ethiopian ones in their stylization and bright colours. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! What struck me most was how each monastery was unique. There is a timelessness in these structures. I have not gone to Ethiopia yet. Hopefully soon. So many places to see and only one lifetime. 🙂

LikeLike

Beautiful photos of Armenia. I was also in Armenia in October and enjoyed visiting most of the monasteries shown here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Armenia is pretty photogenic. I am hundred percent sure we passed each other somewhere, or were at the same place at the same time. 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sanahin was my favourite, with its old world feel. Did you visit on your way to Georgia? Maggie

LikeLiked by 2 people

No, I did not do Georgia. It was only Armenia. I hope to visit Georgia next year. Fingers crossed it happens. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

We absolutely loved Georgia. It’s cites are charming, nature is bewildering and food is delicious. I think seeing Georgia first is why we found Armenian towns depressing. I hope you get there. Maggie

LikeLiked by 1 person

Am sure I will love it. Perhaps I got the order right after all. 🙂 It is interesting how these three countries — Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia — lie right next to each other, yet have such different histories and personalities.

LikeLike

Thank you, Rama, for all the fascinating places you take stay-at-homes like me to 🤗

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is very kind of you to say so. The world needs both: those with itchy feet and the stay-at-homes. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautiful photos ❤️

I wish you much success in the new year. But first and foremost, good health. Blessings from Spain. 🎄🎁🫂

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you! Wishing you much happiness in the new year — all the way from India. 🙂

LikeLike