I was first introduced to the ancient Tibetan religious art form of thangkas in Gyangtse, in the heart of Tibet. It was the summer of 2004. I was travelling solo through Tibet—I had hired a 4X4, got a driver and a guide, and we drove through the majestic Himalaya mountains for seven days, stopping at monasteries, stupas, and temples on the way.

A four-day visit to Dharamshala this June, home to the 14th Dalai Lama and his government-in-exile brought all my memories of Tibet gushing back.

The street that faced the nine-tiered 15th Century octagonal Kumbum stupa in Gyangtse had been lined with stalls. The stupa, by the way, contained a staggering 77 chapels, 108 gates, 100,000 Buddhist paintings, and 1,000 sculptures of the Buddha. In the little shops in the street meanwhile, ancient Buddhist silk applique and cotton paintings, which I was told were called thangkas, were on sale along with other religious paraphernalia such as prayer wheels and prayer flags.

All the thangkas, I remember, looked more or less alike to me. They were filled with intricate mandalas or exotic gods and goddesses from the Tibetan Buddhist pantheon, were framed in rich satin brocade, and had a deep yellow ruffle on the top. Many were dusty. Most looked old. The yellow ruffle, I learnt much later on, opened into a pair of “curtains” which covered the painting. I also remember they were frightfully expensive. Needless to say, I did not buy any. Strange, because even after 15 years I remember them vividly.

Thangka art has its roots in the paintings which decorate the rock-cut caves of Ajanta in India and Mogao in China. Some scholars believe thangka paintings originated in Nepal in the 8th Century AD. The oldest surviving examples of thangka paintings on cloth in Tibet date back to the 11th – 12th Century AD. There are some 20 surviving examples from this second period.

Like all religious art, the primary purpose of thangkas was, and still is, instruction. It does this by depicting scenes from the lives of Buddha, key lamas, bodhisattvas, and other deities, along with the Buddhist concept of the wheel of life. They also serve as a focus for personal meditation, prayer, and rituals. Last but not least, thangkas work as channels for earning spiritual merit and warding off hardship. In the latter case, a lama is consulted who then advises which deity needs to be appeased. After intensive research on its prescribed iconography, the thangka is custom created for the client.

Strict iconographic grids and guidelines define how Buddhist deities are represented in the Tibetan arts.

Rarely painted by lay artists, Tibetan monks were both the custodians and creators of this art form with thangka painting a key component of their requisite skill-set.

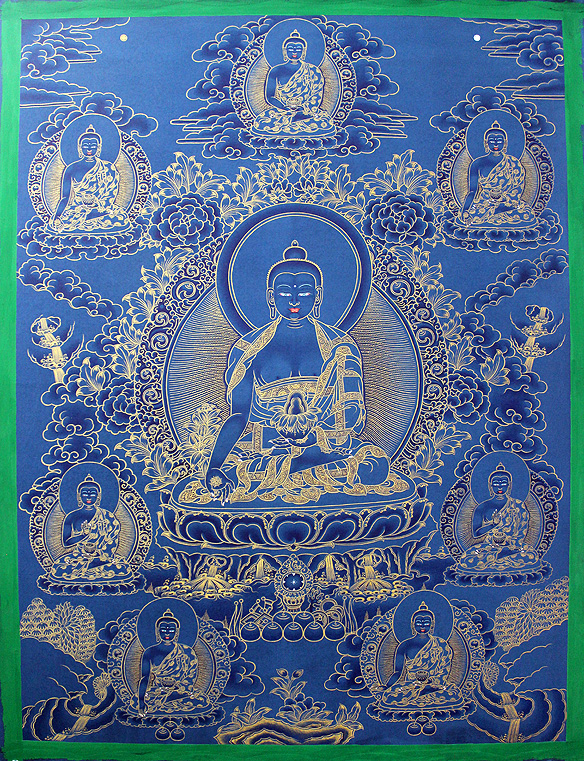

A strict set of rules still define everything in thangka art. From proportions to colours to composition. Why, even all the figures and forms are predefined. A deep understanding of Buddhism and its principles is compulsory to ensure the appropriate mix of form, line, and colour. Is it any surprise then that bona fide thangka master painters are few and far between?

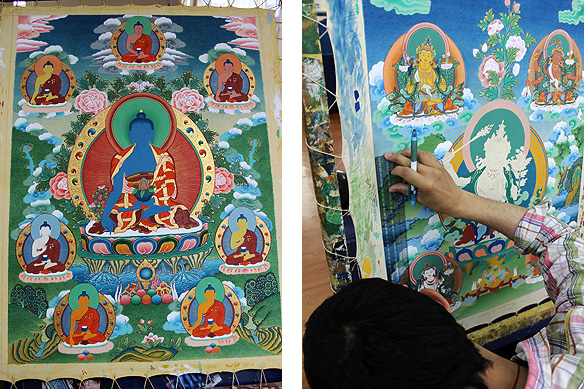

Thangka painting is also a lengthy process. The cloth is first treated with chalk and plaster of Paris, polished with glass, and stretched across a wooden frame. Outlines of the deities using iconographic grids are then drawn onto the cloth. Next, mineral and organic colours, along with 24 karat gold, are applied with fine brushes. A half metre wide painting usually takes around 6 weeks to complete. The brocade frames and ruffles add the finishing touches. Now you know why they are expensive!

When the Dalai Lama took political refuge in India in 1959, a key part of his vision was to protect and create global awareness of Tibetan culture. This was translated into reality in 1995 by Kelsang Yeshi, Minister of the Department of Religion and Culture, and his wife Kim Yeshi through the Norbulingka Institute, a community-based self-sustainable initiative for traditional Tibetan arts.

Though most thangkas are as a rule religious art, they are also used in Tibetan medicine and astrology. In the latter, the stars guide medical treatments and opportune times dictate preparation and dosage. A wonderful collection of 80 medical thangkas, hand-painted copies of the 17th Century originals that were used as modes of instruction, can be seen at Dharamshala’s Men-Tsee-Khang Museum.

An inherent part of Tibetan culture, thangkas have adorned Tibetan homes and temples alike, ranging from the colossal to the homely, since ancient times. The super large ones [mainly in applique] are displayed on special thangka walls in Tibetan monasteries during festivals.

Next time you see a thangka, do take a moment to enjoy them. There are stories and ancient philosophies galore inside their borders. And if you are in Dharamshala, take the journey to the Norbulingka Institute in Sidhpur to see how it all comes together under an artist’s paintbrush—a paintbrush steered by thousand-year-old scriptures. ❤

PS. Maybe I should have bought one of those thangkas which caught my fancy in the streets of Gyangtse, after all. 😊

The palette: Mineral and organic colours with lapis lazuli for blue and 24 karat gold for highlights.

The canvas: Cloth is prepared with chalk and plaster of Paris, after which it is bound to a wooden frame.

A popular composition is the Menri with central figures surrounded by key events or people in their life.

Work in progress: Buddha Amitabha or Buddha of Compassion, characterized with the pink Buddha.

Teaching Buddha, reminiscent of his first sermon in Sarnath where he set the wheel of dharma in motion.

The many stories and characters the thangkas depict [clockwise from top left]: Buddha Shakyamuni, Vajrakilaya, prominent lamas, Dharmachakra [wheel of life].

Medicine Buddha, characterized with the blue Buddha.

Locked in a passionate embrace, Kalachakra [compassion] and Vishvamata [wisdom] are the principal deities of the esoteric Buddhist Kalachakra tantra. Their union manifests the ideal of complete enlightenment.

Norbulingka Institute’s magnum opus: The main temple, Deden Tsuklagkhang, flanked by thangka frescoes and a two-storey high applique thangka to its left. Large monastery and temple thangkas are made with applique instead of paint. The guidelines for composition, form, and colour, however, remain the same.

Front view of the applique thangka at the Institute’s main temple. The composition, comprising of Buddha and 16 arhats or saints, is a labour of love by dozens of the Institute’s artists and took thousands of hours to create.

It’s a beautiful art. I am hoping to get one soon …… A mandala thangka

LikeLiked by 1 person

Luck you! Your home is blessed to have it. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

nice

LikeLiked by 2 people

Reblogged this on Site Title.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the reblog. Appreciated. 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing your knowledge about this art ! Appreciate your work !!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: 36 hours in dharamshala | rama arya's blog

Wow….love this Tibetan art😍. Keep going.👍

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is indeed lovely the way Tibetan art combines imagery with spirituality. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah. Luck you. Exploring everything.God bless. 😇

LikeLiked by 1 person

I need to reblog this

LikeLiked by 1 person

Please do. 🙂 The more who know and understand this art form, the better it is so as to ensure it lives on.

LikeLike

Wow,beatiful is god friend

LikeLiked by 1 person

Welcome to my blog, and thank you for reading my post and commenting on it. Appreciated. 🙂

LikeLike

dear sir please give us your contact number bwe have 40 students from applied arts and we would like to do this thangka painting workshop.

9833785119 my number Riaan jhaverri

LikeLike

Hello Riaan. I do not run these workshops. May I suggest you get in touch with the Norbulingka Institute in Dharamshala and find out if they can run it for you. Best,

LikeLike

Pingback: From Canvas to Cosmos: The Enigmatic Motifs of Ladakhi Thangkas – Oaklores