If you have been to Delhi, India’s capital city, your memories of it would most likely comprise of evocative Sultanate and Mughal monuments. Monuments which are remnants of the multiple cities that flourished here over the past one thousand years.

But no one can deny the city’s most alluring charm, perhaps just a tad bit more than its monuments, is its dense green canopy. A veritable garden city, its broad leafy avenues transform into tunnels of foliage in the monsoons. Large roundabouts embellished with manicured lawns, regal palms, and flowering bushes punctuate the roads at short intervals; roads lined by whitewashed bungalows set amidst their own personal gardens. Expansive reserves called the ‘Ridge’ run wild with jungles. And then there are the countless parks laid out neatly around the city’s monuments and jogging tracts through dark forests.

What if I told you none of this greenery is indigenous to Delhi. That the green cover is the Britishers’ most visible legacy to the city which they made their capital from 12 December, 1911 to 15 August, 1947. Even the Ridge, which Delhiites take much pride in, is draped in the Vilayati Kikar, a Mexican species, planted by the British. Its deep roots kill off any competition, especially Delhi’s native trees.

It is often recounted how prior to the 1920s, Delhi’s landscape was nothing but dusty plains covered in scrub, and on a clear day the eye could see from one end of the city to the other. A bit of an exaggeration perhaps; nonetheless you get the drift. These plains boiled under soaring temperatures and were threadbare. Something which the colonial rulers were determined to fix.

Delhi’s most popular public park was earlier known as Lady Willingdon Park. Thousands of trees were planted in 1936 as a backdrop for a series of Delhi Sultanate monuments.

Britain’s control over Delhi, however, went much before the 1920s. It’s just that it was in the 1920s and onward that they got down to giving the city a makeover. Seeds of British control were sown way back in 1615 when the East India Company received permission from Mughal Emperor Jahangir to set up a factory in Surat. Under the guise of trade, the Company’s powerful army slowly and steadily took over the sea-ports and swathes of the Indian sub-continent.

In September 1803, the British officially took control of Delhi after defeating the Marathas in the Battle of Patparganj, and stayed till August 1947, India’s independence.

This 144-year stretch was not a homogenised whole; it instead comprised of two distinct chapters. Each with its own mood and edifices forming an integral part of Delhi’s multi-layered tapestry. They were the Company Rule and British Raj eras, separated by an event which changed the very equation between the British and India: The First War of Independence or The Indian Mutiny, depending on which side of the equation you saw it from.

DELHI UNDER EAST INDIA COMPANY RULE [1803 to 1857]

After winning the battle in 1803, the British officers of the East India Company settled in the area north of the walled city of Shahjahanabad, namely Kashmere Gate and Civil Lines. Gates were commonly named after the direction they faced. Kashmere Gate, one of Shahjahanabad’s 14 gates, as its name implied, faced Kashmir.

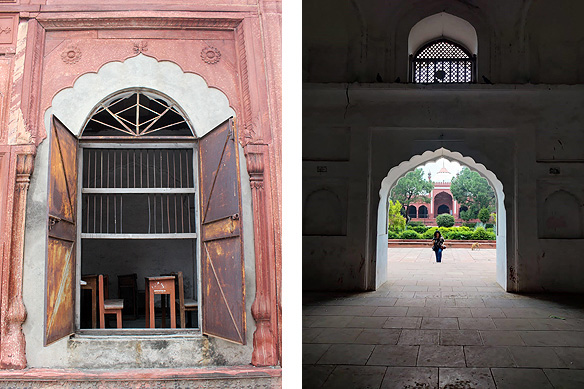

European facade of a haveli in Kashmere Gate.

Before long, a cemetery in 1808 [Lothian Cemetery] and a church in 1836 [St. James Church] came up in the neighbourhoods. Flagstaff Tower, a one-room, castellated signal tower built in 1828 and a Magazine to manufacture and store ammunition took care of the British community’s safety and security.

St. James Church aka Skinner’s Church aka The Yellow Church, is one of Delhi’s oldest churches, and is credited to the Anglo-Indian Colonel James Skinner.

Flagstaff Tower in the Northern Ridge was a signal tower in the Company cantonment area. During the 1857 Mutiny, British women and children took shelter within its walls before leaving for Karnal for safety.

All that remains of the Magazine, once used for manufacturing and storing ammunition, is its gateposts. The British officials blew it up in 1857 to ensure it was not used by the Indian sepoys.

For accommodation, Mughal-era palaces and tombs were put through cosmetic renovations to create homes for the Residents, the East India Company Agents in Delhi. At times, they plastered colonial facades, as in when David Ochterlony, Delhi’s first British Resident, converted Dara Shikoh’s Library into his office [Dara was Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan’s son]. In another instance, William Fraser simply moved into Shah Jahan’s General Ali Mardan Khan’s Palace. Both were in Kashmere Gate.

‘Once the Residency’. East India Company’s first Resident in Delhi, David Ochterlony encased Prince Dara Shikoh’s library in Ionic columns and wooden shutters to use as his office.

Shah Jahan’s General Ali Mardan Khan’s palace was converted into British Resident William Fraser’s mansion. The building is now Northern Railways’ headquarters.

At other times, the renovations bordered on the bizarre such as Sir Thomas Metcalfe’s conversion of Quli Khan’s early-17th Century tomb [in present-day Mehrauli Archaeological Park] into his holiday home Dilkusha.

British Resident Sir Thomas Metcalfe refurbished the 17th Century Mughal tomb of Quli Khan, Mughal Emperor Akbar’s foster brother, into a pleasure retreat and named it Dilkusha meaning ‘heart’s delight’.

Western philosophies and sciences, and English language and literature were introduced in 1824 into the curriculum of Madrasa Ghaziuddin Khan in Ajmeri Gate. One of Asia’s oldest existing madrasas, founded in 1692, it became the Anglo Arabic School, and later its offshoot, the Delhi College, became Zakir Hussain Delhi College.

Anglo Arabic School in Ajmeri Gate traces itself back to 1692, during Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb’s reign. The school is still housed in the original Mughal buildings.

Starting off as the Madrasa Ghaziuddin Khan, it became the Anglo Arabic School in 1824 when the East India Company introduced Western subjects into the, till then, Islamic curriculum.

The early British were particularly fascinated by the exotica of India, and Delhi. Of the mysteries of the Orient, as they say. Amidst large-scale looting and brutal rule built on forceful trade policies, the men, sans their wives, gleefully emulated Indian royalty. They often had multiple native wives, harems, rode elephants, and adopted Indian customs. Detailed records were compiled of flora, fauna, monuments, and the local people. Paintings of these were also commissioned to share with families and friends back home. The more foreign and peculiar, the better.

1857, as mentioned earlier, changed everything. Tensions had already been brewing amongst the Indian sepoys against the Company officers. On 10 May, 1857, things came to a head in Meerut, 45 kilometres north-east of Delhi, when the sepoys in the Bengal army revolted. These sepoys, soon thereafter, made their way to Shahjahanabad’s Red Fort to ask the aging titular Mughal ruler Bahadur Shah Zafar to lead their war of independence. A request he reluctantly agreed to.

What ensued was a raging bloodbath in Delhi, fought over five months, outside Shahjahanabad’s city walls, culminating in British victory. On 14 September, 1857, the British broke open Kashmere Gate and razed the city and the Indian rebel sepoys inside the walls. The Mughal Emperor was sent into exile and his sons executed.

Kashmere Gate still stands today, pockmarked, battered, and bruised by cannon balls; a reminder of India’s first full-fledged, albeit lost, war of independence.

Kashmere Gate, site of the 1857 First War of Independence/ Indian Mutiny pockmarked with cannon balls.

Lothian Cemetery was full by now. A new cemetery named Nicholson Cemetery was set up close-by to house the grave of the chief hero and commander of Delhi’s siege, Brigadier John Nicholson, along with the other officers who were killed in combat. His grave lies near the entrance, guarded by a railing.

Nicholson Cemetery, named after Brigadier John Nicholson, the British army’s war hero who led the forces that blew up Kashmere Gate on 14 September 1857, is an active cemetery.

DELHI UNDER BRITISH RAJ [1857 to 1947]

Of all the things which changed as a result of the 1857 Mutiny, the most significant was who now controlled India from the British side.

India, from this point onward, became a colony directly under the British Crown without the East India Company as an intermediary. With immediate effect the British army in India was reorganized to ensure a revolt of such a nature was never repeated again. In tandem, a social chasm was put up between the colonial rulers and the native Indians that was almost impossible to breach.

Every architectural edifice put up, henceforth, was designed to illustrate this new equation. One of the first of these was the 4-tiered red sandstone Gothic Mutiny Memorial topped with a Celtic cross in the Northern Ridge in Civil Lines. Built in 1863 to honour the British and Indian soldiers in the British army who were killed or wounded in the uprising, the plaques refer to the native sepoys as the ‘enemy’.

Mutiny Memorial in honour of the Company soldiers who crushed the 1857 Mutiny. What is interesting is the detailed information with clear demarcation between the Europeans and Natives.

In Shahjahanabad itself, two-thirds of Red Fort’s Mughal palaces and buildings were demolished. In their place, the new British rulers put up their army barracks. Princess Jahanara, Shah Jahan’s eldest daughter’s garden and sarai were replaced with a yellow-painted brick and stone edifice which served as the Town Hall [1866]. Anglican and Catholic missionary churches mushroomed across the walled city, including the Italian-Romanesque-styled red St. Stephen’s Church [1862], with Delhi’s only stained-glass Rose Window, and gigantic St. Mary’s Catholic Church [1865].

Till 1947, a statue of Queen Victoria stood in front of the Town Hall. St. Stephen’s Church’s red paint is believed to signify the blood of the Christian martyrs who were killed in the 1857 mutiny.

St. Mary’s Catholic Church, now almost 150-years-old, was and still is, an oasis of peace.

Though Delhi was now directly under the British Crown, it still was, in essence, a secondary city in the bigger scheme of things, since Calcutta served as the capital. Kashmere Gate continued to be the hub of residential, social, and commercial life for Delhi’s residents, like it had during Company rule. It continued to be the place to be and be seen.

Keen to educate the native Indians on the lines of European scholarship, premier western-styled institutions started being established. Delhi College, which had moved to Dara Shikoh’s Library in 1844, had been vandalized during the uprising. To make up for the gap created, St. Stephens College and its hostels were set up in 1881, first in a haveli in Shahjahanabad and in 1890 into grand stone buildings in Kashmere Gate.

Left: St. Stephen’s College was designed in the Indo-Saracenic style in 1890. It is the office of the Chief Electoral Officer now. Right: The college hostels built across the road from it.

Indians who sided with the British Crown were rewarded with access to make fortunes. One such was Lala Sultan Singh whose red eclectic mansion soars above the narrow alleys in Kashmere Gate. Sultan Singh Market, founded by him in the 1890s, lined the main street, trimmed with wrought iron Victorian pillars emblazoned with the insignia SS and decorative ornamentation.

Lala Sultan Singh was a wealthy industrialist in Delhi in the 1890s. His home, an eclectic mix of multiple styles, has his initials emblazoned on the front facade in gold.

Delhi was, however, meant for bigger things. At the 1911 Delhi Durbar held in Coronation Park, for which King George V and his consort Queen Mary came to Delhi in person, an announcement was made which shook the whole country. Delhi was to be the coveted capital of the ‘Jewel in the Crown’.

This was not a spur of the moment decision; rather one well thought through. Rebellions against the British were on the rise in Calcutta. Delhi was centrally located. Most salient of all, Delhi had been the historical capital before the arrival of the British, from being the legendary city of Indraprastha mentioned in the Mahabharata to the capital of the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughals. The British wanted to capitalize on this as a means of gaining popular acceptance by their Indian subjects.

A team of architects was soon put together to form the New Delhi Town Planning Committee, headed by the British architect Edwin Lutyens and his associate Herbert Baker. Initially, the plan was to build ‘New Delhi‘ where Coronation Park was. After all, it was in an area [near Kashmere Gate] where the British already had their homes and offices. Even a foundation stone was placed during the Durbar to seal this decision.

Coronation Park, site of the 1877, 1903, and 1911 Delhi Durbars. The statue of King George V was brought here in 1968; it used to earlier stand under the Canopy by India Gate.

Left: Close-up of King George V’s statue. Time has not been too kind to it. Right: The exact spot where King George V and Queen Mary sat and made the announcement that Delhi was to be the new capital is marked by an obelisk.

This idea was soon rejected by the architects. Coronation Park was just not suitable for a capital city befitting the might of the Imperial Crown. Instead, a stretch of land further south, with a natural hill [Raisina Hill] and already occupied by a group of villages, was selected. A deal was struck with the Princely State of Jaipur who owned the land, to which the Jaipur Column in the Viceroy’s House was to be a silent testament.

Lutyens, who had designed London’s Hampstead Garden suburb, envisaged New Delhi as a garden city. Trees were brought in from all over the empire to an arboreum [present day Sunder Nursery] to test their survival rates in India’s climate. Those that passed soon filled the city’s parks and open spaces.

For the main avenues, dotted with roundabouts to break Delhi’s hot winds, species were handpicked for their shade and medicinal qualities: Tamarind on Akbar Road, Neem on Lodi and Aurangzeb Roads, Pipal on Panchsheel and Mandir Margs, and Java Plum on Kingsway.

In the centre of it all was Lutyens’ masterpiece—the Viceroy’s Lodge [present day Rashtrapati Bhawan], the same size as Buckingham Palace and with 340 rooms—flanked by Baker’s Secretariat buildings. The latter, uncannily similar to the Union Buildings he had recently designed in Pretoria. Baker’s Secretariat, unfortunately, stole the limelight from Lutyens work since it was built right in front of the Viceroy’s Lodge, creating a rift between the two men for the rest of their lives.

Viceroy’s House, built between 1914 and 1927, with its Sanchi Stupa-styled bronze dome and fountains on the roof.

Jaipur Column in Viceroy’s House, now the Rashtrapati Bhawan. A reminder of who the previous owners of Raisina Hill and surrounding areas had been. Namely, the Princely State of Jaipur.

In the lawns of Herbert Baker’s Secretariat stand four Columns of the Dominions of Empire. These were gifts from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa, each topped with an identical bronze sailing ship—a reminder of the British Empire’s maritime history.

In front of Lutyens and Baker’s colossal edifices was the Great Place [present day Vijay Chowk] where Kingsway [present day Kartavya Path], a broad boulevard lined by trees, fountains, and gardens intersected with Queensway [present day Janpath]. At the other end of Kingsway was India Gate, a War Memorial Arch in the middle of the hexagon-shaped Princes Park, surrounded by mansions of the main Princely States.

Under a Canopy, next to the Arch, stood a towering statue of King George V calmly gazing out at his dominion. Council House [present day Parliament House], another of Baker’s creations, completed the majestic ensemble.

Kingsway [Rajpath after 1947 and Kartavya Path after 2022] cut through the Central Vista, ending at the 1921 Roman-styled India Gate dedicated to the Indian soldiers who had died at war.

The Canopy at India Gate housed a towering statue of King George V right up to 1968.

Though Lutyens and Baker are the only two who are often credited with designing the new capital, numerous other talented architects pitched in with their creativity. Henry Alexander Medd gave Delhi its grand English churches such as the rose-red Sacred Heart Cathedral [1930] and tiered Cathedral Church of the Redemption [1931]. Walter Sykes George gave the city Lodi Colony as residences for the bureaucracy.

Sacred Heart Cathedral [1930] just outside Connaught Place is a Roman Catholic church and the biggest church in Delhi.

The Anglican Cathedral Church of the Redemption [1931], arguably Delhi’s most beautiful church.

Connaught Place’s bespoke tailors, cinemas, ballrooms, art galleries, and European bakeries provided the new city its new social hub for the winter months. Come summers, these establishments along with Delhi’s residents moved to Shimla, the British Raj’s Summer Capital. It was a routine followed stringently till 1947.

New Delhi’s Connaught Place was designed not just as a shopping arcade but a residential area with entertainment and social amenities as well.

Connaught Place today brims with brands and restaurants behind the rows of Doric columns, much like it did 80 years ago.

It took twenty long years, from the day the announcement was made, to complete New Delhi. Much longer than expected; World War II, in-between, had necessitated the diversion of funds and human resources. The city was finally inaugurated on 10 February, 1931. Sixteen years later, the British colonisers for whom it was made, had to leave and go back to their homes across the seas.

Four years after the curtain fell, in 1951, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, in a bid for a final farewell, both to the past and the departed, established the Delhi War Cemetery. Before this, the graves of the Christian European soldiers who had died during battle in World War I and World War II had been scattered throughout Northern India. In addition, a hand-written book kept in a Memorial at the site, recorded the names of the 25,000 Indian soldiers who had fought on behalf of the British, as their subjects.

Delhi War Cemetery, deep in the city’s cantonment area, bids good bye to the British and Indian soldiers who fought in the two world wars, and indirectly, to Delhi’s chapter of colonial rule.

– – –

Over the past 75 years, since India’s independence on 15 August, 1947, the names, as well as purpose of many of the structures built by the British rulers have changed. King George, together with statues of four other Viceroys from across the city, have moved to Coronation Park, albeit, some with broken noses. Public buildings and bungalows have transformed into government offices, colleges, schools, and museums. Once elitist areas have been democratized, now open to people of all class, caste, and creed.

Even with all the changes though, one look at the giant leafy trees and one is reminded of the Britishers’ 144 years in the city, and maybe, their most enduring legacy—Delhi as a garden city. 🙂

– – –

Travel tips:

- It is possible to stay in a colonial-era hotel in Delhi: Maidens Hotel [1903] in Civil Lines and The Imperial [1936] in Janpath. Both are 5-star hotels and priced on the steep side.

- The Imperial serves a spread of English-styled High Tea daily in The Atrium which is considered a bit of a Delhi institution.

- Intach Delhi runs a series of heritage walks through most of the precincts covered in the above post. The walks led by Ratnendu Ray are especially insightful. These sites are also very doable as independent explorations.

Lovely compilation and presentation Rama. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Narayan. Much appreciated. This post is the culmination of multiple heritage walks and self-guided trails. I wanted to weave it all together into one narrative. Am glad you feel it has worked. 🙂

LikeLike

Much I didn’t know, here. In half a dozen visits to Delhi, I’ve never really seen much of the British legacy other than the area around Connaught Place.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I hope you get to explore the ones you have not yet visited on your next trip to the city. None of these sites are marketed and, hence, tend to be missed out on by most.

There are actually a lot more which I have not included. Either because they are pretty decrepit such as Gol Market, meaning round market [Edwin Lutyens, 1921] and currently under restoration, or a bit bland such as the Gol Dakh Khana, meaning round post office [1885], or completely off limits to the casual visitor such as the Metcalfe House in Civil Lines [1835]. Those I have included in this post can easily be seen independently or on a heritage walk to the area. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know about the off limits ones, in that I wanted to see the Writer’s Building when I was in Kolkata, but found out it’s now a government building and there was no chance of going in.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I have yet to explore the colonial part of Kolkata. One day, for sure. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

A very good wander around the city!! 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Welcome to my blog. 🙂 Thank you for taking the time to comment. Glad you liked the post! There is so much to see in Delhi. Unfortunately, most of it gets ignored. The colonial side especially gets sidelined, and it is a pity becsuse it is an incredibly interesting side to the city.

LikeLiked by 2 people

You are very welcome! It was an interesting read!

Ha, yes, maybe give it a century and people might pay the 19th century buildings greater attention. 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hehehe. True. 😄

LikeLiked by 1 person

So many amazing places in Delhi. When we were there everyone told us to skip Delhi because there was nothing to see. We saw more than many tourists, but you’ve given an extensive list of places I’ve never heard of but would love to see. Great post! Maggie

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Maggie. 🙂 Oh, there’s loads to explore in Delhi. After being the capital city of multiple empires which ruled the sub-continent over the past one thousand years, I have found it to be multilayered like no other in the country. I’ve been exploring Delhi since March this year, on nearly every weekend, and my bucket list is sill not all ticked off. 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a comprehensive guide! Now I know where to go on my next visit.

I didn’t know that we can get so close to the Rashtrapati Bhawan. I stopped at the Secretariat Buildings because there were so many barricades on Rajpath on that day. I thought the area is restrictive to the public 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Len, you can, in fact, go inside the Rashtrapati Bhawan. Intach Delhi (link given under travel tips at the end of this post) runs heritage walks in English inside the building. The government runs walks inside daily in Hindi. There is so much to see in this city! Glad you found this post useful and has given you ideas for your next travels to Delhi. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the tips, Rama 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

For all the history and architectural marvels Delhi has, I feel like it’s often avoided by many international tourists. I myself have been intrigued by this city probably since my early years of blogging. And the fact that now it has one of the most extensive metro systems in the world only makes it even more appealing. One day, hopefully!

LikeLiked by 1 person

One day hopefully! I must admit I have been pleasantly surprised and incredibly impressed by what the city has to offer. It has something for everyone and that too loads of it, especially when it comes to heritage. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: a heritage buff’s guide to the eight cities of delhi | rama toshi arya's blog

Amazing. One of my favorite cities in India and I will certainly be using your posts on my next trip to aid in my exploration of it. I am so happy to have found this all!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Am so glad you enjoyed the read, Eva. Means a lot. Wishing you happy travels in the city. 🙂

LikeLike

Delhi has been my stomping ground through the most formative years of my life. Loved your blog. Here is my perspective

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for stopping by and your kind words. What an interesting post you have written with your grandpa as the tour guide. 🙂 Truly enjoyed the read!

LikeLiked by 1 person

wow great. Interesting to know about this Dehli. Never been India, but now i know little bit from your Blog.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Welcome to my blog, gederedita. Hope you make it to this part of the world, some day soon. 🙂

LikeLike

Pingback: a travel guide to colonial delhi – Fidel Management Services

Pingback: a self-guided walk through shimla, the british raj’s summer capital | rama toshi arya's blog