Don’t mistake the swarms of visitors at Hampi as tourists. Not all of them are. Most of them are pilgrims. For in Hampi, nestled in a surreal boulder-strewn landscape in north Karnataka, each stone is sacred.

Irrevocably tied to the Hindu epic Ramayana, Hampi traces itself back to a mystical past. Anegundi, the expanse across Hampi’s Tungabhadra river, was then known as the vanar [monkey] Kishkindha kingdom ruled by King Sugriva. In the epic, Sugriva’s commander Hanuman and army of monkeys helped Rama rescue his wife Sita from the demon Ravana.

Fast forward a few millennia from otherworldly mythology to historical facts substantiated by Kannada inscriptions and journals of Italian merchant Nicolo di Conti [1420], Persian diplomat Abdur Raazaq [1442], and Portuguese traveller Domingo Paes [1520].

Hampi, was now the capital of the wealthy, secular, and immensely powerful Hindu Vijayanagar empire. The richest city in the Indian subcontinent and the second biggest city in the world, it ruled a realm that encompassed modern-day Karnataka, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu.

Its kilometre-long markets which stretched out from towering gopurams [temple gateways] overflowed with diamonds and gold. Traders from China and Persia sold their silks and camels in its stalls, whilst literature and visual arts flourished under royal patronage. Established in 1336 by the two brothers Harihara and Bukka, Vijayanagar had become a force to reckon with. Under its poet-king Krishnadevaraya [1509 – 1529] the empire and its capital reached their zenith.

And then one day it all came crashing down to a brutal end. 23 January, 1565. The Battle of Talikota.

The four neighbouring Deccan Sultanates who had hitherto been busy squabbling amongst themselves decided to unite and declare war on the Vijayanagar empire. Hampi was attacked, razed, and looted—an exercise that took six months to accomplish because of the city’s scale and amount of wealth. Burnt, and emptied, it was then abandoned. The Sultanates figured it best for none of the four to occupy the conquered city to keep peace amongst themselves.

Despite moving the capital thrice after the pillage, the Vijayanagar empire never regained its lost glory. It died a final death in 1646.

Over the centuries, people from neighbouring areas trickled into Hampi and turned the forgotten ruins into their homes. Close in their heels were western hippies enamoured by the site’s exotic. But then with the introduction of the 1972 Antiquities and Art Treasures Act, the Archaeological Survey of India [ASI] marked it as a major historical site, followed by a UNESCO listing in 1986.

These developments have transformed Hampi, spread over 40 sq. kilometres and dotted with 1,600 surviving monuments, into one of the world’s largest open-air museums. Residents are presently forbidden to dig, though treasure-hunters continue to scour the ruins at night. Most structures are temporary, and music is muted by law near its centerpiece, the Virupaksha Temple. It is not unusual for resorts and cafes to be demolished at short notice for an excavation.

Here are Hampi’s stories. Some told. Some untold. For never was there a site where mythology, history, an archaeological site, and a present-day village replete with laid-back cafes live happily side-by-side. And where it is a bit hard to say where one begins and the other ends.

Seven layers of fortifications around the palace area, punctuated with gateways where customs officials collected entry taxes, seven villages, and seven weekly markets. That’s Hampi’s city-plan in a nutshell. One such gateway was the monumental Bhima’s Gateway, a fabulous specimen of military architecture, dressed up with an effigy and panels of Bhima [from the Hindu epic Mahabharata] inside its angular walls.

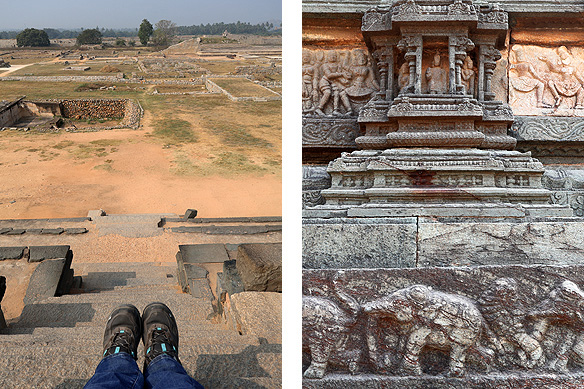

What happens when an international trading metropolis and an age-old Hindu festival celebrating the victory of good over evil come together? Mahanavami Dibba happens.

The Vijayanagar kings celebrated the ninth and final day of Navratri, in which Goddess Durga defeats the demon Mahishasura, with great pomp and ceremony. Foreign dignitaries were invited. Governors pledged their allegiance. Markets brimmed with goodies and livestock from across the world, and there was dance and food and music. How do we know all this, you may well ask. Scenes from the festivities were carved for posterity onto a massive schist-encased platform from which the king addressed the event.

Scenes from the Mahanavami celebrations make a second appearance on the enclosure walls of Hampi’s magnum opus—King Devaraya II’s 15th Century Hazara Rama Temple.

Meant for royal use, the temple itself is sheathed in three bands of exquisite bas relief friezes which narrate the entire Ramayana. Don’t have time to read the epic. Just circumambulate the Hazara Rama Temple thrice. Apart from its stunning carvings, Hazara Rama Temple, with Rama as its chief deity, also served as a political statement. Seen as a hero, Rama was not just a deity the kings wished to emulate, but the temple’s presence reiterated the rulers were his reincarnation.

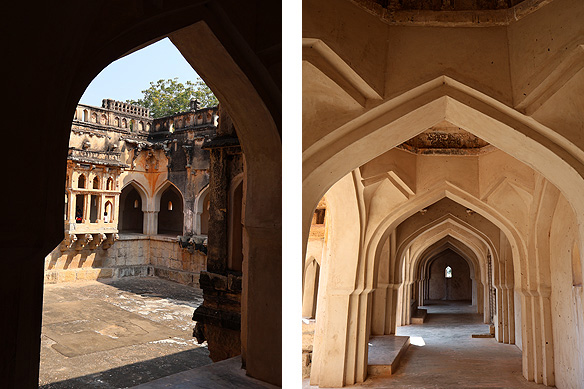

Step into Hampi’s Zenana [ladies] enclosure and you may well wonder if you’re still in staunchly Hindu Vijayanagar. Turkic-Persian lobed arches and ornate domes merge with Indic lotuses and kirtimukhas in the Lotus Mahal, Queen’s Bath, and Royal Stables to create an architectural ensemble that sits in stark contrast to the rest of purist Hampi.

Hampi’s secular Hindu kings had no qualms in borrowing design elements from their Muslim neighbours. But they were also savvy enough to limit their tastes to their private quarters and keep public edifices in line with their subjects’ beliefs.

“… the mighty storm of Garuda’s wings

turns the whole world upside down,

dispersing sins like heaps of cotton.”

~ King Krishnadevaraya [1509 – 1529]

Can a city have two masterpieces? Yes, because Hampi does. Started by King Devaraya II in the 15th Century and further decorated by King Krishnadevaraya, Vitthala Temple is Hampi’s most popular attraction, and for good reason. True to its second patron, the poet-king, the temple is sheer poetry with a stone chariot to house the Garuda of his poems. The 56 musical pillars of Ranga Mantapa, with each cluster of eight pillars [one instrument and seven notes] carved out of a single rock, would have provided the music to accompany his words.

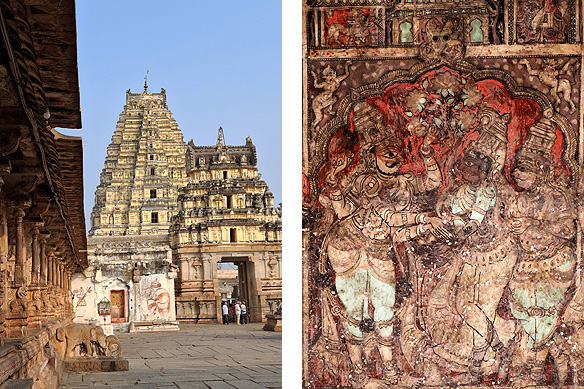

Virupaksha Temple, Hampi’s oldest place of worship dates to the 7th Century. When all of Hampi was burning, this one site remained unscathed and continues to function today as it has done for the past 1,400 years. Dedicated to Pampa, a local goddess, she was married to Shiva [Virupaksha] and thereby incorporated into the Hindu pantheon. The very name Hampi is derived from Pampa.

No one is quite sure why Virupaksha Temple was not destroyed in 1565 when the others were. Was it because it preceded the Vijayanagar empire and, thus, perceived as unrelated? Was it the dense village around it that formed a barrier? Or was it an effigy of Varaha [Vishnu’s boar avatar] at the entrance which stopped the Muslim soldiers in their tracks since Islam considers the boar to be impure.

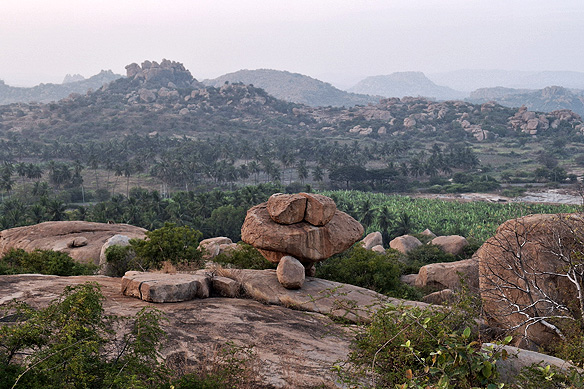

From time immemorial, mythology has tried to explain the seemingly unexplainable. Including Hampi’s surreal terrain. According to a local legend, Hanuman and his vanar sena [monkey army] took rocks from here to build Ram Setu—the bridge over the oceans to Ravana’s Lanka. They ended up with more than they needed, and dumped the extras higgledy-piggledy all over Hampi.

For the Vijayanagar sculptors millennia later, these boulders ended up being a boon from which they could hew gigantic effigies of Ugra Narasimha [6.7 metres tall] and Kadalekalu Ganesha [4.6 metres tall] in the round.

No, you have not been transposed to south-east Asia and are still very much in Hampi. The gopuram and vimana sculptures in Krishna Temple, built by King Krishnadevaraya in 1513 to commemorate his victory in Orissa, look uncannily like those in Cambodia!

Hampi’s palaces and temples were mostly carved out of the indigenous golden-hued sandstone, with green schist and cuddapah used intermittently for embellishments. Except for one—the gigantic 5-tiered stepped water tank or Pushkarini fed by aquifers inside the royal enclosure made wholly of black schist.

The interesting part is not that there is a tank, but the markings which specify row number, direction, and sequence to facilitate assembly since the slabs were brought in from distant Andhra Pradesh’s quarries.

Prior to Hampi’s two-century-long celebration of Hinduism, Jainism had flourished in the royal capital. Though soon sidelined, their temples continued to stand, hinting at a tolerant society led by secular rulers. Less ornate than their Hindu counterparts, these 14th Century temples are scattered across the city’s ruins, over Hemakuta hill, and in forgotten pockets such as the Ganigitti and Parshvanath Temples.

Ganigitti, identified by its stambh, translates to ‘the oil women’s’ temple because when ASI took it over a group of women were running an oil-production unit in the temple complex.

For over a decade, priests have been chanting the Ramayana at the Malyavanta Raghunatha Temple. Come hail or rain. 24 hours, 7 days a week. A short climb up brings one to a huge cleft flanked with two rows of shivlings and nandis.

When Rama and Lakshman set out to search for Sita, they needed a place to take refuge from the monsoon rains. Out came Rama’s bow and this was where the arrow landed. The two brothers spent four months on this mount and worshipped Shiva at this very cleft. Needless to say, it is one of Hampi’s most mystical sites.

Who says only the wealthy can be patrons? Hampi’s largest shivling at 3 metres tall was commissioned by a Badavi meaning ‘poor’ peasant woman. Look closely and you will see Shiva’s three eyes etched on it.

Everyone knows about Hampi’s Hazara Rama, Virupaksha, and Vitthala Temples. But only a handful know of the Achyutaraya Temple tucked behind Matanga hill. Built in 1534 during the high point of the Vijayanagar architectural style by a government official in King Achyutaraya’s court, it was Hampi’s last grand project before the city’s downfall. You will most likely be the only visitor amidst the evocative ruins.

Look what has been recently unearthed at Hampi. Bhojana Shala aka a dining hall, replete with built-in plates and bowls for the guards/ soldiers’ use on special occasions! An active archaeological site, there are new discoveries made here all the time. Some are mundane. And some path-breaking. One can only wonder at what more stories lie under the boulders and palm-fringed dusty planes.

With this I also come to the end of my post on Hampi and my Hampi-Aihole–Pattadakal–Badami series. I hope you enjoyed them. I sure enjoyed writing them.

❤

– – –

Travel tips:

- Staying there: I stayed at the Mango Tree Homestay [+91 94832 15189] in Kamalapur Village. Clean rooms, wonderful hosts, and delicious breakfasts. The family also own Hampi’s cult-status Mango Tree Restaurant. Another not-to-be-missed eatery is Ganesh Old Chillout near Virupaksha Temple.

- Getting around: I explored Hampi, seated pillion on the motorbike of my incredibly knowledgeable guide Bhanu Prakash. He can be contacted at +91 94494 09070.

- Do visit the ASI Museum. It houses some of the finest sculptures and artefacts found in and around Hampi.

Another one I never got to. It looks amazing! (and so does the dosa!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Mick. Hampi had long been on my bucket list based on other travellers’ experiences. It lived up to its hype. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brilliant pics

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your kind words. 🙂

LikeLike

The first time I became aware of Hampi was from a French magazine in 2006 or 2007, and I remember thinking what an utterly intriguing place it looked! In 2015, I finally got the chance to see the ruins, and they truly were impressive. Your photos bring back some fond memories from my trip, and yes, Achyutaraya Temple was very quiet when my friend and I went.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry for the delay in responding. Was in Saudi Arabia for 18 days. Another stunning country. 🙂 Am glad you got to experience Hampi. It is really one of a kind.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There is a certain stylistic similarity to Angkor, which I have just reviewed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

True. Lost cities of our world. Will read your reviews. 🙂

LikeLike

Excellent photoblog. I really appreciate the blend of images and history.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you liked it. Hampi has great stories and is very photogenic. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great read and beautiful captures!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Jyothi. Am happy you enjoyed it. 🙏

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi. This is a terrific essay. I knew nothing about the subjects you write about. I can only imagine the amount of research you did.

Neil S.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. I had a fabulous guide who helped me uncover Hampi’s secrets. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a lovely read with beautiful visuals! 🤍✨

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for stopping by and your kind comment. 🙏

LikeLiked by 1 person