In the heart of Baroda, now called Vadodara, within the royal Gaekwad family’s once sprawling grounds is the Kirti Mandir or Temple of Fame. The gigantic stone cenotaph was built in 1936 to ensure their ancestors’ posterity. A sun, moon, and a map of undivided India etched on a bronze globe are perched on top of its shikhara—a sovereign declaration of the spread and timelessness of Gaekwad rule.

But the cenotaph is weathered now and forgotten. It is visited on the rare occasion when a royal family member passes away and is brought to the adjacent cremation grounds to be burnt and then transposed into a plaster-of-paris bust placed in one of the rooms lining the passageways.

A lone 70-year-old guard, who has spent the last 60 years serving the royal family, with his one-year-old grandson’s arms wrapped around his neck unlocks the large doors should perchance a traveller land up at the temple’s doorstep. But this post is not about the royal family. I will write about them on another date. This one is about the art and artist whose mythological masterpieces decorate the walls inside Kirti Mandir.

Nandalal Bose, pronounced Nondo-lal Boshu (1882 – 1966) is no stranger to a Bengali. But outside this esoteric circle he remains largely unknown in modern India. And yet, together with Rabindranath Tagore, Amrita Sher-Gil, and Jamini Roy, he was one of the pioneers of Modern Indian Art. His paintings were declared a national treasure and part of the “nine masters” by the Archaeological Survey of India in 1976.

What distinguishes his work—inspired by the murals at Ajanta Caves—is his “Indian style of painting.” The style, associated with national awakening and independence, was led by Abanindranath Tagore as a counter-move against the Western art styles taught in art schools during the then British Raj. Reflecting Indian values in Indian art, it originated in Kolkata and Santiniketan, and later came to be known as the Bengal School of Art.

Scenes from Indian mythologies in narrative panels and dynamic compositions wrap the white walls of Kirti Mandir in vibrant egg tempera frescoes painted in mineral colours. Stylized figures tell stories that have come down through the ages to the Indian. Come let me show you around these panels and share with you the magic of Bose’s art. 🙂

Whilst some parts of the frescoes are in impeccable condition, the paint peels away in others. But these time and weather induced blemishes do not diminish the panels’ aesthetic beauty one bit. My favourite is that of Mirabai in her Marwari dress, deep in meditation. Which one do you like the most?

Panel 1: Gangavatarana—Valmiki Ramayana

The story of Gangavatarana, descent of the River Ganga, is mentioned in various ancient Hindu scriptures including the Ramayana written by the Hindu sage, Valmiki. The descent is associated with Lord Shiva, the Lord of Destruction.

Replete in rich iconography, Shiva is represented here with three faces symbolising the three aspects of time: past, present, and future. His five hands hold the trident, a bowl of nectar, poison, conch, and a damaru. The sixth hand is extended in a consoling gesture. A garland of human skulls resembling flowers drapes around his arms and waist.

To the right of Shiva is Brahmas Kamandalu, a vessel for carrying water. From it ganga jal cascades over Shiva’s head, down to his feet. Ganga herself is shown in multiple forms. Firstly over Shiva’s head, secondly in the middle as Bhogavati, the Ganga which flows underground and Mandakini, the Ganga which remains in heaven, and lastly kneeling down at Shiva’s feet.

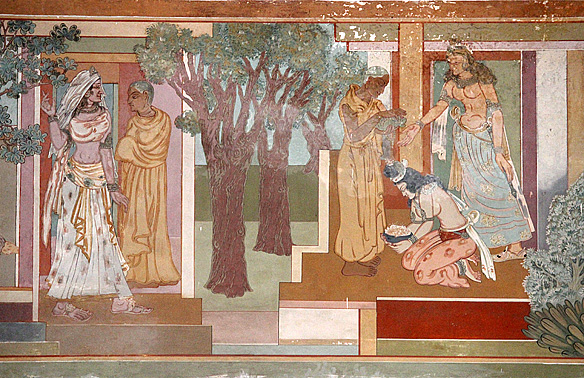

Panel 2: Natir Puja

Natir Puja was a dance-drama written and directed by Rabindranath Tagore based on a Buddhist legend. It recounts the story of Sreemati, a dancer in the court of Ajatashatru.

The story goes as follows: Following King Bimbesara and his younger son’s renunciation of worldly charms in favour of meditation and prayers, Ajatashatru decides to wipe out all traces of Buddhism and forcefully establish Hinduism as the state religion. Sreemati, meanwhile, is a devoted Buddhist and continues with her practice against all court orders. Sreemati is one day selected to dance at the stupas for the vasant purnima celebrations. However, she gets so engrossed in her dance she starts discarding both her garments and ornaments one by one, and is eventually left only wearing the wrap of a bhikkhuni, a fully ordained female monastic.

Panel 3: Mirabai

The fresco on the wall opposite Gangavatarana depicts the life of bhakti saint Mirabai, Lord Krishna’s legendary devotee and a mystic poet. Born in 1498 in Rajasthan, she wrote about 1,300 passionate devotional prayers dedicated to Krishna during her lifetime.

In the first frame Mira is seen in full Marwari dress, deep in meditation [top]. In the second frame she gazes beyond a lake, her mind elsewhere. She is next shown leaving her home dressed in a white sari and with an ektari in her hand, in the company of other devotees [middle image]. The last frame has her at the Dwarkadheesh Temple where according to legend she dissolved and merged with the idol of Krishna inside [above].

Panel 4: Battle of Kurukshetra

On the fourth wall is the Battle of Kurukshetra fought between the cousins, Kauravas and Pandavas. The central frame [top] shows Krishna persuading Arjun to fight on the lines of the Bhagwad Gita. To its left, Abhimanyu, ordered by his uncle Dharma to break the chakravyuha set by Dronacharya is shown surrounded by the Kaurava army, fighting valiantly without any weapons [this blog post’s title picture]. In the right frame [above], Dhritarashtra and Queen Gandhari lament the death of their sons, their bodies burning, turning into ashes.

The stories in this panel illustrate that everything ultimately perishes and turns to ashes. The only thing one can leave behind is “Kirti” or fame. And hence the name Kirti Mandir was given to the family cenotaph.

The setting for Nandalal Bose’s masterpieces: Kirti Mandir or Temple of Fame built by Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III in honour of his ancestors (1936)

very informative with some beautiful pictures. Thanks for sharing!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Ashish, thank you for stopping by and commenting. Glad you enjoyed Bose’s masterpieces. They truly are a visual delight. 🙂

LikeLike

What a beautiful words and art this blog is. I love art and I love travel, and just reading this one post I am so interested in more.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a lovely comment, David & Laura Speer. All the more meaningful because it is coming from someone who shares the same passions as me. Thank you. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

unique and relly buityfull

LikeLiked by 1 person

Bose’s art has indeed a unique look and feel. The stylisation and combination of art with verses of literature turn the panels into story-telling at its finest.

LikeLike

Amazing one✌ Indian history and art is one of those thing which make Indian’s to be proud of.!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely! We are pretty blessed to have such incredibly rich art and history as our heritage. Kirti Mandir with its frescoes is a lovely reminder of the treasures we live amidst. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Art History blog

Lovely frescoes and information

LikeLiked by 1 person

And who would have thought looking at its outer facade that Kirti Mandir housed such treasures. I certainly did not, and once in, I could only gawk and gasp in awe. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well life does throw some surprises ☺

LikeLike

Pingback: the mythological frescoes of nandalal bose in vadodara | aadildesai

EXCELLENT WORK!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for stopping by! 🙂

LikeLike

Wow very knowledgeable.

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: the 6 untold treasures of vadodara | rama arya's blog

Thank you so much for sharing these images and information.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Amal Sircar, the Kirti Mandir with its frescoes is an absolute treasure house for an art lover. Am glad you enjoyed the read and paintings. 🙂

LikeLike

Pingback: preserving a disappearing heritage: the bagh cave paintings at bhopal state museum | rama arya's blog

Pingback: the painted and sculpted caves of ajanta | rama arya's blog

Great read thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you enjoyed the read, Melanie. 🙂

LikeLike